Mahler and Wagner Songs In New Arrangements

Mezzo-soprano Kindra Scharich and the Alexander String Quartet brought two new arrangements of song cycles by Gustav Mahler and Richard Wagner to the La Jolla Athenaeum on Friday night, June 27, 2016. These well crafted arrangements were adroitly written by the quartet’s first violinist, Zakarias Grafilo.

Entering the Athenaeum’s Joan and Irwin Jacobs Music Room on a chilly, foggy “May Gray”evening, we were embraced by the comfort of its bygone Central European ambience, as if we were about to be entertained in the salon of one of those legendary pre-World War I Viennese residences. Expecting Dr. Freud to be in attendance or perhaps Adele Bloch-Bauer to walk out of her famous Klimt painting and sit down to enjoy the concert with us would not have been unreasonable. The atmosphere was one of true and unassuming Teutonic Gemütlichkeit.

Charming yet meandering introductory remarks by Scharich gave us some interesting stories concerning the genesis of the Mahler arrangement. Second violinist Frederick Lifsitz was left to ably fill us in on the additional historical context of the songs.

Although the individual songs of Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder do not literally form a song cycle, they have been performed together for so long that it is difficult not to think of them as one. The original versions for singer and orchestra or piano are so well known, in fact, that creating a new arrangement for mezzo-soprano and string quartet took courage and even a little moxie. Most listeners will inevitably refer back to the originals in their sonic memory, although listening to Grafilo’s work made me forget that his is even an arrangement. The violinist/arranger handled the harmonic and instrumental requirements so deftly that his version stands as a valuable, unique contribution to the chamber-vocal repertory.

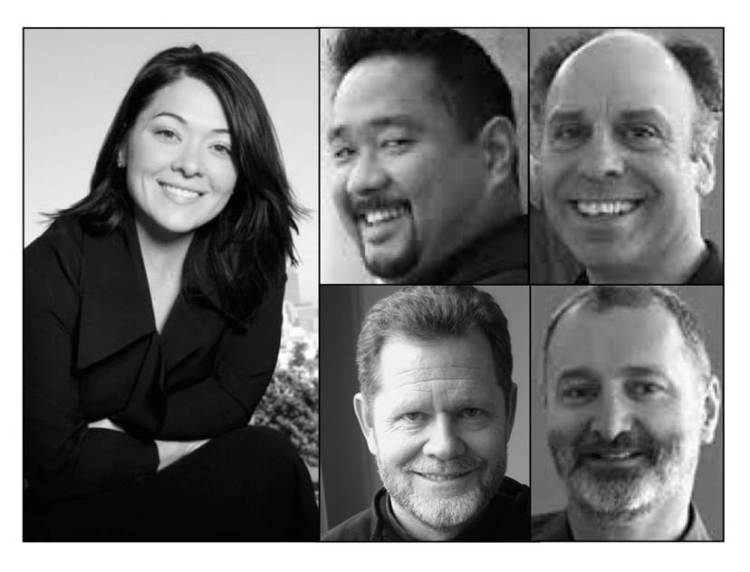

Kindra Scharich, left; the Alexander String Quartet, right. Used by permission of La Jolla Athenaeum

Scharich’s singing of these exquisite examples of Lied proved exemplary. The size of her dusky voice was ideally scaled to the string quartet accompaniment, never overwhelming either her colleagues or the listeners in the small room. With nearly perfect German diction, she successfully delivered the deeper meaning of the poetry in a remarkable way.

It was easy to sense the singer channeling Rückert’s poems in an almost Stanislavsky-like manner, actually becoming the voice of the poet. This impressive display of method acting was most evident in the final song, “Ich bin der Welt abandon gekommen” (“I have lost track of the world”). The world-weariness of this song almost makes a person want to give up the struggle of living and go to sleep forever.

After the intermission, Scharich performed Grafilo’s arrangement of Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck-Lieder, five settings of poems by Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of one of Wagner’s extremely wealthy patrons, Otto Wesendonck. Historians are divided on whether or not Wagner and she were having an affair while he was under Otto’s sponsorship, but judging from Wagner’s proclivities, it would be hard to imagine that they were not. The intensity of ardor is often imputed to the conception of Tristan und Isolde, which Wagner was working on at the same time.

Although the graceful and masterful touch of a true poet does not appear in the Wesendonck-Lieder, Scharich gave these songs the same deeply committed and technically assured performance she gave the Mahler song cycle. The lower strings were represented in exemplary fashion by the quartet’s cellist, Sandy Wilson, who used his outstanding bow technique to create an entire world in the bass clef.

If Wagner’s craft as an art song composer did not equal Mahler’s, the two cycles nevertheless made for a deeply enjoyable evening of music-making in precisely the right locale.

Yochanan Sebastian Winston, Ph.D. has performed throughout the United States, Europe and Latin America. His repertoire spans classical, jazz, klezmer, new age, contemporary, rock & roll and pop and is very active as a composer. Dr. Winston holds a Ph.D. from the UCSD, a Diplôme from the Conservatoire National de Region de Boulogne-Billancourt (France), and a Master’s and Bachelor’s of Music from the Manhattan School of Music in New York City.