Jackson Pollock is Coming to SDMA!

Jackson Pollock. “Convergence,” 1952.

Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1956]. © 2014 Pollock-Krasner Foundation/ Artists Rights Society, New York. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

You better watch out,

you may even cry.

I’m telling you once

and you’re gonna die!

Jackson Pollock is coming to town!

While Pollock sleeps six-feet under,

his all splattered “Convergence” is approaching

as is Gorky’s surrealist “…Cock’s Comb”

and a Mark Rothko nuclear bomb.

Jackson Pollock is coming to town!

No, you are not crazy.

You may think it is a dream:

one might swing with Frida’s “…Monkey”

or at a “Carnival of Harlequins” scream.

And you’d better watch to spy

Gauguin’s mistress—perhaps to die!

Yes, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery’s most prized artworks are coming from Buffalo, New York to “winter” at the San Diego Museum of Art in Balboa Park. The traveling exhibition Gauguin to Warhol: 20th Century Icons from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery includes paintings that every school art history textbook dare not exclude: Paul Gauguin’s “Spirit of the Dead Watching.”(1892), Giacomo Balla’s “Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash” (1912), and Arshille Gorky’s “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb” (1944). Other iconic artworks from the Albright-Knox’s stellar collection will be vacationing in San Diego as well.

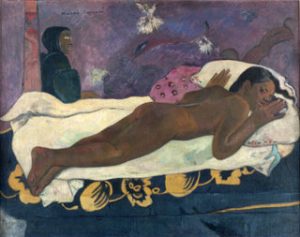

Paul Gauguin. “Spirit of the Dead Watching,” 1892.

Oil on burlap mounted on canvas. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [A. Conger Goodyear Collection, 1965]. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

Gaugiun’s version features Tehura on a bed laying nude on her stomach. At the left of the painting is both an ominous black-cloaked, old woman gazing upon the overtly sexualized young woman and the words “manao tupapau,” which literally translates as “The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch.” The scene was inspired by an entry in Gauguin’s diary where he recounts coming home to find Tehura filled with fright: “Might she not with her frightened face [taken] me for one of the demons and [specters] of the Tupapaus, with which the legends of her race [cause her] people sleepless nights?” (Noa Noa, Louvre manuscript, p.110). Gauguin amplified the emotion of the painting through color by using a moody background of purples and a shock of yellow on one of the bed’s blankets. Tiny clashing phosphorus green spirits of the dead with flashing white coronas float above the girl.

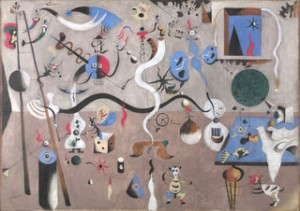

Joan Miro. “Carnival of Harlequin,” 1924-25.

Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1940.] © 2014 Succession Miro S.L. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

“In the canvas certain elements appear that will be repeated later in other works: the ladder, an element of flight and evasion, but also of elevation; animals, and above all, insects, which I have always found very interesting; the dark sphere that appears to the right is a representation of the globe, because in those days I was obsessed with one idea: ‘I must conquer the world!’; the cat, who was always by my side as I painted. The black triangle that appears in the window represents the Eiffel Tower. I tried to deepen the magical side of things.” —J. Miro

(Quoted from Albright-Knox Art Gallery. <http://www.albrightknox.org/collection/collection-highlights/piece:miro-carnival-harlequin/>)

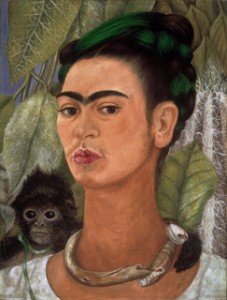

A Frida Kahlo will be vacationing here, too. Her “Self-Portrait with Monkey” (1938) features a monkey with its arm warmly embracing her neck. Kahlo was unable to have children due to her 1925 involvement in a crash between a bus and a streetcar. Agile spider monkeys, who the artist likened to children due to their playful natures, appear in several of her paintings. This emotional portrait features the artist and her pet monkey, Fulang-Chang. This work along with Kahlo’s other self-portraits with monkeys are interpreted as being metaphors for Frida’s maternal longings.

Frida Kahlo. “Self-Portrait with Monkey,” 1938.

Oil on masonite. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [Bequest of A. Conger Goodyear, 1966]. © 2014 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera

& Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. I./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

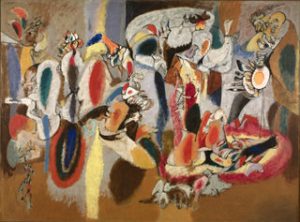

Armenian-American Arshille Gorky’s most famous masterpiece “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb” (1944) will also be avoiding Buffalo’s harsh winter. Inspired by Joan Miro’s surrealist biomorphic, abstract shapes as well as belle peinture (beautiful painting from the French tradition). The over 6-foot tall by 8-foot wide painting looks like multicolored scribbles. Knowing the title of the works let’s one potentially see both fried egg and chicken-like shapes. Up-close, one can see Gorky’s thick and thin painting handling that was inspired by the Romantic era’s superior colorist and draftsman artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Gorky and his best friend Willem de Kooning had studied the belle peinture in both Ingres’s “Comtesse d’Haussonville” (1845) since its first public display in 1935 [at the Frick Museum] and “Odalisque in Grisaille” [at the Metropolitan Museum] when it went on display in 1938.

Arshile Gorky. “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” 1944.

Oil on canvas. Image Courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1956]. © 2014 Estate of Arshile Gorky / Artists Rights Society, New York. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

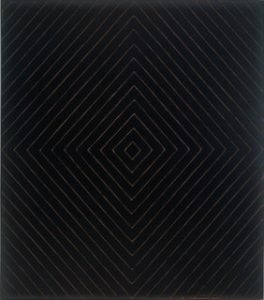

Frank Stella, “Jill,” 1959.

Enamel on canvas. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. [Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1962]. © 2014 Frank Stella I Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

Stella thought that his paintings of consecutive black lines arrested and controlled a viewer’s gaze to prevent the viewer’s eye from wandering around his canvases. Hand painted with a four-inch house painter’s brush, “Jill” features a diamond in its center with consecutive slightly imperfect radiating individual black diamond lines painted on unprimed canvas. When viewing it, one’s eyes do become glued to the center of the painting. The painting essentially becomes flat and target-like rather than being a traditional painting with a foreground, background, and subject. At an optimum viewing distance, one can, indeed, only see the whole painting all at once like a flat emblem, thus proving Stella’s famous dictum.

Avoiding the Buffalo’s winter chill will also be paintings by Matisse, Modigliani, and Picasso. An early radiant “Head—Red and Yellow” (1962) by Roy Lichtenstein and 100 cans of Campbell’s soup (“100 Cans,” 1963) by Andy Warhol will also be avoiding hypothermia. Enjoying our moderate climate will also be Jackson Pollock’s enormous, over 8-foot tall by 13-foot canvas of multiple hues of dripped and thrown paint entitled “Convergence” (1952).

One of the artist’s most complex paintings both in use of color and space. Its frenetic energy literally put the “action” in Action Painting. Let us hope that the energy of “Convergence” can withstand San Diego’s all too laid-back attitude concerning fine art.

The quality of artworks in Gauguin to Warhol: 20th Century Icons from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery shine so brightly that one could potentially view them in the dark with a mere candle and still come away giddy at having seen them. Art lovers need no encouragement to see this show and will love it—even if installed horribly on the ceiling of the museum. Those who are indifferent to art should see this exhibition and perhaps the bonfire of artistic genius on display will kindle a new appreciation for art within you.

A holiday present such as Gauguin to Warhol coming to the San Diego Museum of Art is, indeed, like Santa Claus coming to town!

Gauguin to Warhol: 20th-Century Icons from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery will be on exhibition from 4 October 2014 through 27 January 2015.

Kraig Cavanaugh lectures about art history—specializing in Modern & Contemporary Art—as well as being an instructor of color theory, design, and studio art. He has curated numerous art exhibitions, authored exhibition catalogues, and written art reviews for several other print and online journals including “Artweek” (USA) and “Selvedge” (UK) magazines. Cavanaugh is also an invited member of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art (United States division), which is an NGO in official relations with UNESCO.