Edo de Waart Leads San Diego Symphony in Impressive Season-Opening Concert

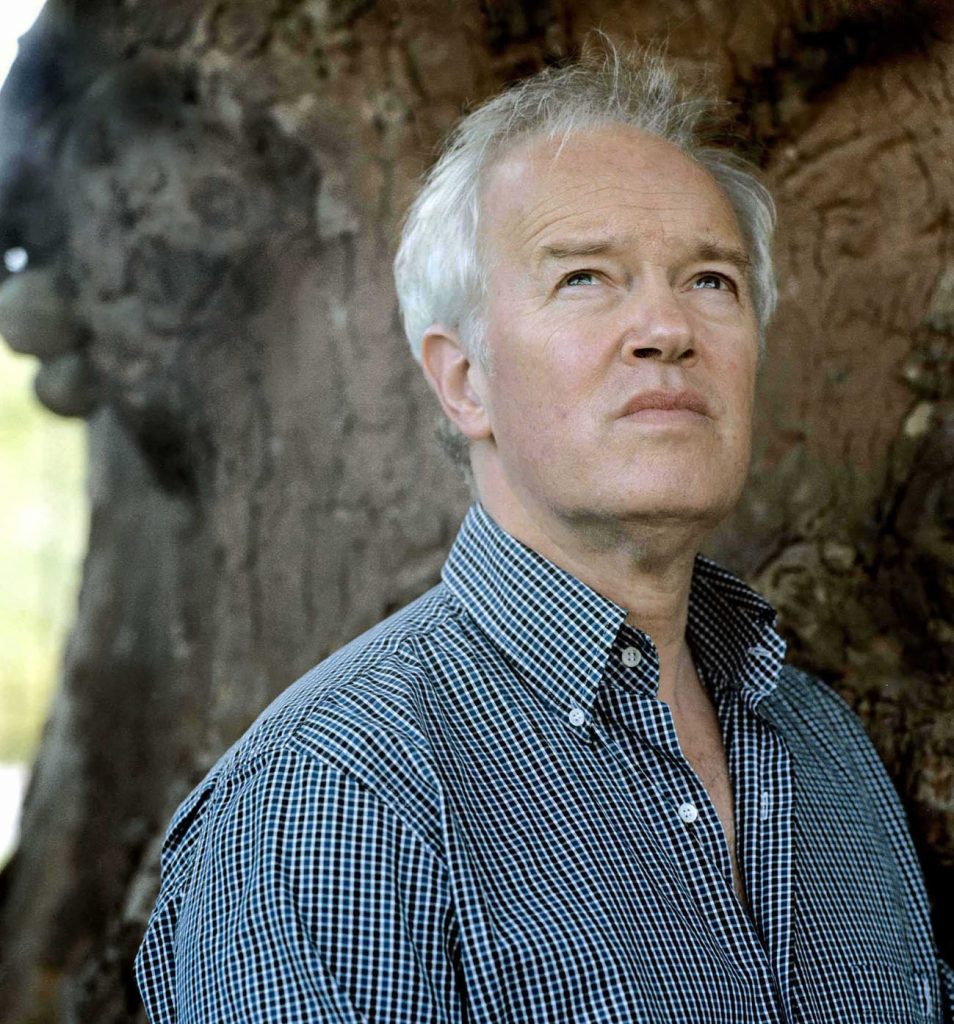

Esteemed conductor Edo de Waart returned to the San Diego Symphony to lead the orchestra through an impassioned season-opening concert Friday (October 6) at the Jacobs Music Center. His fourth guest appearance in the last three years only confirmed the impression from his previous visits: his congenial authority on the podium produces an unusually impressive level of performance from the local orchestra.

Conducting the San Diego Symphony, de Waart has amply demonstrated his prowess with major works from Beethoven to John Adams, but Friday he chose to concentrate on the heavy-hitting Romantics: Wagner, Liszt and Richard Strauss. From the orchestra’s swaggering, brassy ramble through the Overture from Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg to its virtuoso tone painting in Strauss’s “Ein Heldenleben,” the players sounded in top form. De Waart appears to get exactly what he requires from the San Diego Symphony, without micro-managing every phrase and nuance. De Waart shared the spotlight with guest soloist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, who did the honors in Franz Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major. Another familiar and welcome guest artist on the San Diego musical scene, Thibaudet can be counted on for brilliant keyboard technique trademarked by his imperturbable sheen of elegance. These virtues propelled the Liszt concerto, although the soloist’s most winning contributions were not dazzling cadenzas but his tranquil, reflective interludes and transitions, including a transcendent dialogue with Principal Cellist Yao Zhao. Around Zhao’s gracefully sculpted, slightly plaintive lines Thibaudet wove shimmering, rhapsodic commentary.In truth, Liszt’s eccentric, single-movement concerto gives all the compelling themes to the orchestra, placing the pianist in the role of decorative enhancement, although early in the concerto, the soloist contributes a hearty flourish of gnarly, low bass themes that will find their fullest expression in the composer’s “Totentanz,” which he completed a few years after the Second Piano Concerto.

But the seamless, ardent collaboration of Thibaudet, de Waart and the orchestra produced a captivating performance of a work that counters so many of the listener’s typical piano concerto expectations. The soloist declined to offer an encore, in spite of the audience’s insistent approval of his performance.

I am tempted to think that given contemporary tastes, the barnburning early tone poems of Richard Strauss are more appreciated by conductors than by audiences. The composer’s hubris—Strauss composed the shamelessly autobiographical “Ein Heldenleben” (“A Hero’s Life”) at age 34, before he had written any of the operas that actually made him heroic—reveals itself in this piece in over extension and self-congratulation, repeating episodes from the early portion of the work at the end, after a virtual catalogue aria of quotations from other Strauss compositions.

Nevertheless, de Waart proved a seasoned guide on this orchestral biographical journey, giving apt Wagnerian sweep and grandeur to the propulsive themes that animate the tone poem and clarifying the textures in the contrasting tranquil sections, notably the gorgeous slow cantilena that represents the composer’s wife Pauline, the successful soprano, played with persuasive finesse by Concertmaster Jeff Thayer. And when that extensive violin solo develops feisty complexity, because the soprano did have a combative side, Thayer sleekly navigated those technical challenges with the same silvery tone with which he opened the cantilena.

To judge from the score, it would appear that the sole source of conflict in the hero’s life were unreceptive music critics, depicted by jagged and slightly discordant nattering themes emitted primarily by the woodwinds. We are told that the critics of Strauss’s time took these musical jabs as insults, but since so much music of the last century indulged in worlds of discord far more extensive, I took these short and comparatively mild moments of dissonance as welcome contrasts to the countless mellifluous themes the composer churned out in his lengthy opus.

Like the San Diego Symphony’s vibrant account of Stravinsky’s ballet “Petrushka” last May under Charles Dutoit, this traversal of “Ein Heldenleben” under Edo de Waart showed the orchestra’s powerful command of the expansive, late Romantic repertory that any first class symphony is required to display. Kudos especially to the strings for their glowing sonority and to the horn section for its strength and stamina throughout the work. Strauss’s father was one of Munich’s most virtuoso horn players, and the composer placed the highest expectations on those instrumentalists. Principal Horn Benjamin Jaber and his crew deserved the wild cheers they received when de Waart gave the horns a solo bow during the post-performance applause.

As if Strauss’ music and its backstory were not enough to engage the audience, a constantly changing series of artistic projections by Chicago artist Mike Tutaj were displayed across the upper levels of the Copley Symphony Hall stage during the “Heldenleben” performance. Although most of these designs were geometrically abstract and monochromatic, there were some physical images and flora in the style of Aubrey Beardsley. Given the bright lighting of the Copley Hall stage, however, I found their contribution muted at best.

This performance of the San Diego Symphony was given on Friday, October 6, 2017, in the Jacobs Music Center’s Copley Symphony Hall in downtown San Diego. It was repeated (without the Wagner Prelude) on Saturday, October 7, in the same venue.

Ken Herman, a classically trained pianist and organist, has covered music for the San Diego Union, the Los Angeles Times’ San Diego Edition, and for sandiego.com. He has won numerous awards, including first place for Live Performance and Opera Reviews in the 2017, the 2018, and the 2019 Excellence in Journalism Awards competition held by the San Diego Press Club. A Chicago native, he came to San Diego to pursue a graduate degree and stayed.Read more…