Dystopia and Utopia: Theatre Reflects the Times

As 2017 dawns, there has been much commentary about how we may be living in dystopian times – that is, we may be experiencing the opposite of a utopian era where we might be encouraged to think that “this is the best of all possible worlds.” Of course, the arts often reflect the public mood, and, indeed, theatre has provided a wealth of plays that are staged in dystopian settings.

On the other hand, hard times are often counteracted by fluff and optimism. Witness, for example, the popularity of Depression-era theatre and film that put pure fluff on the stage, often in the form of singing and dancing with wild abandon, in stark contrast to the social realism being portrayed in a number of dramatic productions of the period.

A sampling of plays and musicals, many of them from a recent London theatre trip, provides fodder for analysis. I’ll start with the dystopian examples and then examine with the optimistic ones.

Directors often use current events to inform what’s on stage, and Melly Still, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s director for its production of Cymbeline, found significant similarities in the complex plot of one of Shakespeare’s last plays and the “Brexit” debate that was going on in the U. K. when the production was in preparation for the 2016 Stratford-Upon-Avon summer season (it aired in cinemas in September and played an encore run at the company’s Barbican Theatre home in London, where I saw it).

Shakespeare set his romance against a historical event: the empire that was created by Julius Caesar and expanded by Augustus Caesar. Shakespeare imagined that Augustus’ decision whether to take Britain through invasion was fraught with political intrigue and even entailed an attempt to undermine the royal household through an attempt to seduce Innogen, the daughter of the monarch. Ms. Still used the play’s machinations to encourage audience members to draw parallels between the threatened Roman invasion and the feared invasion of the European Union that seemed to have spurred the Brexit movement. Her creative team also set much of the play in dark and unsavory conditions. She was also deliberate in casting to make particular points: Cymbeline was played by a woman, and Innogen’s betrothed was played by a man of Arab ancestry, for example.

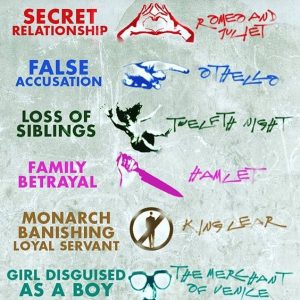

Clocking in at more than three hours, plus intermission, the complicated plot and dreary setting could have encouraged audiences to run for the door. But, the company tried to play it as light as they could. See, for example, the infographic reminding viewers that many of Cymbeline’s plot devices had appeared in earlier Shakespeare plays as well.

Clocking in at more than three hours, plus intermission, the complicated plot and dreary setting could have encouraged audiences to run for the door. But, the company tried to play it as light as they could. See, for example, the infographic reminding viewers that many of Cymbeline’s plot devices had appeared in earlier Shakespeare plays as well.

The other dystopian example from London was a production of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut at Covent Garden’s Royal Opera. First produced in 2014, Jonathan Kent’s production set the turgid drama in contemporary times, portraying the title character as a naïve young woman whose head is easily turned by wealth and attention. She’s noticed by a man whose primary qualities are sexy good looks, and once the two have connected the opera turns into one long love duet, with tragic consequences. Director Kent apparently wanted to comment on how sex, wealth, and the sleaze that accompanies it have tarnished passionate love in contemporary society.

The 2014 performances apparently made Mr. Kent’s point, though reviews were mixed. In 2016, new leading singers were in the roles, their costumes were ill-fitting, and quite a bit of the concept had become muddled. The finale was staged, as in 2014, on a desolate rock ledge, perched high above the stage floor. It looked so distressed that the singing couldn’t compensate. Given that in this opera Puccini was experimenting with Wagner’s concept of the “music drama,” I anxiously awaited the arrival of Die Walkure’s Magic Fire to bring some life to the proceedings.

So, the Royal Shakespeare Company made a dystopian vision work, while the Royal Opera did not. It’s a tricky bit to pull off, I think.

The hugely contrasting piece of fluff currently playing in London is a major revival of the musical Half a Sixpence. The last traditional British musical to transfer to Broadway, in 1965, prior to the revolution led by Andrew Lloyd Webber with Jesus Christ Superstar (1971), Half a Sixpence became renowned for bringing British pop star Tommy Steele to the West End and Broadway stage. Written originally by David Heneker and Beverley Cross, the revival featured a revised book by Julian Fellowes and additional music and lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe. It was initially produced by Cameron Mackintosh at the Chichester Festival and then transferred to London when it proved to be a hit.

The story is a trifle about romance across the classes at the turn of the 20th Century. The score is pleasant and hummable. The dancing is lively. And, the producers found its young lead, Charlie Stemp, in the chorus and transformed him into a bona fide star.

He knows it, too. He flirts with the audience every chance he gets.

The show is a throwback, albeit a charming one. It has been criticized as such, and I imagine some will stay away, as it is about as far from Hamilton as one could get.

There were also a couple of shows that could classified as “in between” on the dystopia/utopia scale. One ultimately came down on the utopian side, while the other ended in a more dystopian manner.

The ultimately utopian show was the London production of the Cyndi Lauper/Harvey Fierstein musical, Kinky Boots. Based on a British film about an industrial town that is about to lose its largest manufacturer, a shoe factory, it begins as a kind of fantasy dystopia but then shifts into almost happy-go-lucky mode after a drag queen named Lola (Matt Henry) helps to transform the business. Ms. Lauper’s score deftly mixes pop and Broadway elements and even draws some tears with the ballad, “Not My Father’s Son.” The closing anthem, “Raise You Up/Just Be,” projects about as utopian a vision of individualism in a diverse world as might be imagined.

On the other side of this divide was a musical (of all things) titled A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer. Developed by the theatre collective, Complicite, this original musical (Book by Bryony Kimmings and Brian Lobel, Music by Tom Parkinson, Lyrics by Bryony Kimmings) follows a diverse group of individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer, particularly a mother whose child has been taken from her for testing. The setting features a room of three white walls with doors spaced equally around. Above each door is a sign that reads “Exit,” (instead of “Way Out”). The doors are like the ones in Jean Paul Sartre’s play, No Exit: they work when patients are called but won’t open at other times.

The performance starts out on a mostly hopeful note, and the songs are upbeat and feature colorful costumes (such as ensemble members dressed as cancer cells). Eventually, cancer starts to get the best of some of the patients, and the colorful and perky cancer cells turn into large grey blobs that begin to take over the room. The music turns anxious and angry as the story heads toward catharsis. The waiting room becomes a place of despair, and by the end dystopia looms.

Like the other dystopic examples I’ve mentioned, a major goal seems to be encouraging the audience to talk about the experience afterward. It worked in my case. I don’t usually strike up conversations with other theater-goers, but I did this particular evening, ending up describing my own cancer experience and how I did and didn’t identify with the characters onstage.

A major function of dystopic theatre seems to be pushing audiences to connect current difficulties with what’s being presented on stage. Similarly, utopian theatre seems to function either to relieve current anxieties or to celebrate situations where everything works out for good in the end. Both kinds of theatre can be useful in hard times.

Does this sampling of the current London theatre scene foretell what might happen in San Diego theatre? I think only time will tell. I do expect, however, to see our theatre artists reacting to our current cultural and political milieu.

In addition to reviewing theatre for San Diego Story, Bill also reviews for TalkinBroadway.com. He is a member of the San Diego Theatre Critics Circle and the American Theatre Critics Association. Bill is an emeritus professor in the School of Journalism and Media Studies at San Diego State University.