Dohnányi, Historical Seating, Produce a Riveting Beethoven Fifth

If the four-note thunderclap – da-da-da-DUM – that opens Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony does indeed evoke Fate knocking on our door, that fearsome presence arrived at Copley Symphony Hall in a hurry last Friday evening. Conductor Christoph von Dohnányi, leading the piece without a score before him, launched the first movement with a brisk tempo that riveted both players and audience. I have rarely seen – or heard – the San Diego Symphony playing with so much concentrated clarity as it displayed in the opening pages of what may well be the most famous piece of music in the Western world.

Perhaps its hawk-eyed focus on the conductor could be attributed to his international fame and long history with this music. Or perhaps the ensemble was responding to an unfamiliar seating configuration, for Maestro Dohnányi had re-seated the orchestra in what a symphony spokesman accurately calls the “historical” arrangement, with first violins and second violins facing each other across the conductor, the cellos to the left of the firsts, the violas to the right of the seconds. Double basses had been moved to an elevated platform on the left (looking at the stage) and the woodwind choir was at center with the timpani behind them and the brass also behind them, a little to the right.

The St. Petersburg Philharmonic utilizes the same arrangement, as does the Vienna Philharmonic, as local audiences saw when those ensembles played here on tour in recent seasons.

What’s the point, you ask?

A good part of the reason is probably just the power of tradition. Other factors may be the ability to produce a more powerful violin sound by moving the seconds closer to the audience, and giving the violas and cellos the advantage of a straight-line shot in projecting their playing toward the audience, massing the lower strings so that they can play with more volume without fear of drowning out the second violins.

Whatever the reasons, it worked. The Orchestra had a density and texture – particularly in the two Beethoven works that book-ended the evening – that deepened and enriched its presence, even as it probably forced the players to listen to each other in a more concentrated way.

Intense concentration has its drawbacks, however, for it can also produce early fatigue. Dohnányi followed a pattern in all four movements of the Symphony, starting with a burst of sometimes nearly-rushed energy and then gradually subsiding to a more foursquare tempo as the movement proceeded, and as fatigue set in, so did problems with rhythmic steadiness and intonation. This is not to diminish the orchestra’s overall admirable traversal of this over-familiar work, merely to point out some of the problems along the way to a rousing conclusion that brought the audience to its feet, with repeated calls for the conductor, who enthusiastically acknowledged excellent playing from the orchestra as a whole. He also gave richly-deserved bows to principal flute Rose Lombardo and principal bassoon Valentin Martchev, whose solos were, in one word, superb.

Another Beethoven work opened the program, the third of the overtures Beethoven wrote for his only opera, then called Leonore. Eventually to meet the world as Fidelio in 1814, this, his only operatic child, bedeviled the composer from the time he began writing it in 1803 until he made its final revisions and let it go, with yet a fourth overture (the so-called Fidelio overture) in 1814.

The Overture tells the story of the entire opera in music that is both despairing and starkly powerful. Dohnányi and the orchestra gave it plenty of both, but it was the sustained atmosphere of hushed expectancy that gave the performance its special character. This is music that can gallop out of the performers’ control with just a nudge, but both conductor and players found the key to a gripping performance in understatement and restraint. The orchestra managed something that few orchestras achieve: amazingly soft playing while maintaining a solid, substantial sound.

Pianist Emanuel Ax joined the Orchestra at the concert’s mid-point for Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat Major, K. 271. Written in 1777, when Mozart was 21 years old, the work may well have been a young man’s flirtatious calling-card to a young woman named Mademoiselle Jenamy, while she visited and played in Salzburg (the “Jeunehomme” sobriquet later given to the concerto seems to have been a corruption of her name.) She was accompanied by her father, a court dancer, and Mozart’s music is filled with dance rhythms, including a sublime minuet that stops the last movement rondo in its tracks and whirls both player and listeners away for four variations before Mozart returns to the work at hand as if jumping back onto a speeding train.

Emanuel Ax is rightly famed for his Mozart playing, and his performance shone with a patrician finish, although from time to time it was clear that he would have been happier with faster tempos. I kept hoping that Mozart’s ardent wooing and aching yearning might come through with a little less elegant restraint, but it is ungrateful to complain when playing at this high level is offered so open-handedly by everyone on the stage.

[box] Editor’s note: SanDiegoStory.com welcomes Marcus Overton and thanks him for his comments and analysis of the recent San Diego Symphony concert. [/box]

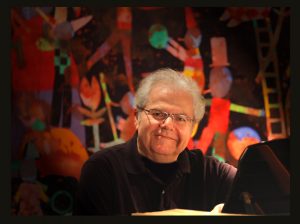

In a 50-year professional career, Marcus Overton has crossed disciplinary lines to work in theatre, opera, dance and broadcasting. Trained as an actor by Alvina Krause at Northwestern University, he made his professional debut in the title role of Shakespeare’s RICHARD III. Work as a director in both theatre and opera (Lyric Opera of Chicago, Chicago Opera Theatre, San Diego Opera) followed, as well as administrative positions at the Ravinia Festival, the Smithsonian Institution’s performing arts program, and the general manager’s post at Charleston’s Spoleto Festival USA. On South Carolina’s famed ETV radio network, he has been producer and host of Spoleto Today for 20 years, as well as an Emmy Award-winning producer of six television specials about the Festival. He is currently a Consultant for Special Projects at the La Jolla Music Society.