The “Point Loma Pause” as Art: Ikaros at the WOW Festival

It’s called the Point Loma pause: the 10 or so seconds when a plane roars over Point Loma, and you have to stop mid-sentence. Every time it happened during “Ikaros,” the piece that Third Rail Projects created for the La Jolla Playhouse WOW Festival, the three performers went into stillness and looked up. I looked up, too, seeing this everyday occurrence as if with fresh eyes; marveling at the miracle of flight.

Third Rail Projects is acclaimed for site-specific work in its New York home and internationally. For the WOW Festival, which took place this year at Liberty Station, Third Rail’s creative team—led by Co-Artistic Director Tom Pearson—chose a location on the bay under the flight path. And they infused it with meaning, connecting the ground where we stood to the history and romance of flight with exquisite visual imagery, every-gesture-counts dance, and an evocative recorded sound score.

Third Rail Projects is acclaimed for site-specific work in its New York home and internationally. For the WOW Festival, which took place this year at Liberty Station, Third Rail’s creative team—led by Co-Artistic Director Tom Pearson—chose a location on the bay under the flight path. And they infused it with meaning, connecting the ground where we stood to the history and romance of flight with exquisite visual imagery, every-gesture-counts dance, and an evocative recorded sound score.

There’s an air of mystery as we gather after dark near the edge of the water. We’re given headsets and a pamphlet about the local flora and fauna … with the intriguing title “Garden of Asterion” and a map with a mazelike pattern. Googling later reveals that Asterion was the mythical minotaur, who lived in the labyrinth designed by Daedalus; the same Daedalus who made the wings worn, fatally, by his son, Ikaros (usually written in English as Icarus.)

A guide, holding the kind of wand-like light used to guide planes on the tarmac, beckons us down a trail. Through the bushes, we glimpse a man (Justin Lynch) jumping on a trampoline, holding … is it a toy airplane? No, when he joins two other dancers (Andrew Broaddus and Mary Madsen) in a clearing, we see that the object he took aloft was a slender, articulated wooden manikin. Ikaros, I think, as echoing voices in Sean Hagerty’s score say, “My father pushed me from a tower” and talks about wings made of wax and feathers.

In a series of stops at clearings, the three performers, clad in flight jumpsuits, slowly corkscrew up from the ground, play airplane, stand on benches with their arms winging out, and take one another skyward in seemingly effortless lifts. Lynch stands behind Madsen, and both do semaphore arms—quickly, they could hit each other, but they don’t. The movements are relatively simple yet performed with impeccable clarity.

In a series of stops at clearings, the three performers, clad in flight jumpsuits, slowly corkscrew up from the ground, play airplane, stand on benches with their arms winging out, and take one another skyward in seemingly effortless lifts. Lynch stands behind Madsen, and both do semaphore arms—quickly, they could hit each other, but they don’t. The movements are relatively simple yet performed with impeccable clarity.

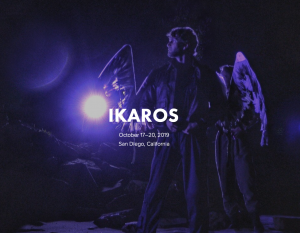

Images and associations accumulate. Madsen unrolls a spool of rope; Broaddus guides it into the shape of a labyrinth. Madsen puts on a leather flight jacket with a propeller on the back and a white scarf, becoming Amelia Earhart. Then Lynch is wearing enormous white wings (designed by Bennett C. Taylor), facing the edge of the land.

Even pedestrian moves convey a sophisticated choreographic intelligence. For instance, when Madsen unrolls the rope for the labyrinth, she holds her elbows bent and the spool high, at about her forehead, and the unspooling feels like a ceremony. And when a plane passes overhead, and the dancers go into stillness, it’s as if the world holds its breath.

Award-winning dance journalist Janice Steinberg has published more than 400 articles in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Dance Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. She was a 2004 New York Times-National Endowment for the Arts fellow at the Institute for Dance Criticism and has taught dance criticism at San Diego State University. She is also a novelist, author of The Tin Horse (Random House, 2013). For why she’s passionate about dance, see this article on her web site, The Tin Horse