Shoestring Live Arts Fest Delivers World-Class Dance

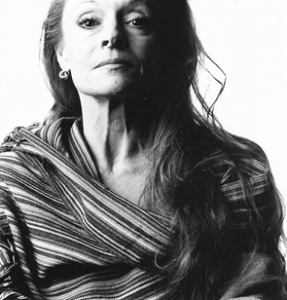

Christine Dakin

The Live Arts Fest put on by Jean Isaacs San Diego Dance Theater is truly a shoestring event—on Saturday, Isaacs was working as a stagehand, handling props. So it’s all the more remarkable that the ten-day festival offered a rich palette of work by international artists, including Christine Dakin, longtime principal with the Martha Graham Dance Company, doing Graham’s legendary solo, “Cante Jondo.”

Dakin’s appearance on Sunday, the final night of the Live Arts Fest, capped a weekend of memorable performances. On Friday, we got evocative work from Mexicali artists. On Saturday, Katie Stevinson-Nollet, here from Connecticut, did solos created for her by major choreographers. And Dakin shared the Sunday program with the dynamic Tijuana troupe Lux Boreal.

Friday: “Susurros de La Memoria” (Whispers of Memory)

Three travelers, two men and a woman, carry old suitcases in this hypnotic piece by Manuel Torres, whose career includes extensive performing and, currently, being dance coordinator of CEART Mexicali. The traveler-dancers (Felipe Geraldo, Oscar Martinez, and Carolina Zavala) sit and balance on the suitcases, do headstands in them, and half-lie inside them, their arms and legs swimming in the air.

As composer Max Estrada alternates between playing lyrical piano and generating electronic sounds, the dancers at first seems to occupy private worlds, even when they’re doing unison suitcase maneuvers—including, for the men, a dazzling flying leap from a prone position. Then the men connect in wheeling capoeira-style kicks. To tender piano (like the sound track of a romantic French movie), Zavala and a third man (Torres, a riveting presence) do a searching pas de deux. And Zavala has an intensity as bright as her red hair in a solo where, with hip swivels and turns, she does quick changes of direction and level.

At the end, the travelers reach toward us, and are they asking for something or offering us a gift? Not knowing is part of the allure of this atmospheric dance.

The program also included four CEART students doing a piece by Guillermo Bedolla. In “Estropico” (Screen), the young women are constantly distracted by their mobile phones, as a recorded text—excerpts from a leftist speech?—distracts us from the dance. Static moments seem true to our screen-obsessed times, but feel like dead zones in the dance.

Saturday: “Coming to the Surface”

“Immersion.” Photo: Jeff Teitler

Katie Stevinson-Nollet began her career in San Diego and is now a professor at the University of Hartford; she also directed Full Force Dance Theatre for over twenty years. This program of five solos, each by a different choreographer, brought the work of some exciting dance makers to the White Box. And it showed off Stevinson-Nollet’s considerable range, as she finished one dance, did a quick metamorphosis (changing costumes behind an onstage curtain), and emerged with a radically different style.

Pure beauty isn’t a regular feature of contemporary dance, but Adam Barruch’s “Immersion” has a loveliness that—with Stevinson-Nollet’s drapy white top and pants—made me think of Isadora Duncan. And it evoked a dreamlike procession of images. At one moment, Stevinson-Nollet is a swimmer, her arms fluidly folding into her core, then whipping out. Kneeling, or circling her arms as if carrying a basket, she seems an acolyte at a Greek temple. This was my first taste of work by Barruch, a young artist who already has a knockout resume, and I’m eager to see more.

“Self, guided” Photo: Jeff Teitler

A few minutes behind the curtain, and Stevinson-Nollet appears in a hillbilly-meets-flower-child getup for David Dorfman’s comic “Self, guided.” (Costumes were designed by Mary Sheldon.) Talking aloud about the choices one makes in creating a dance—”How much longer should I do this?”—she moves with deliberate awkwardness, holding her hands in rabbit paws, choking herself, tracing her breasts. A quizzical look on her face, she announces, as if to convince herself, “I feel happy. I feel safe,” in this piece that—in characteristic Dorfman style—uses humor to go deep.

Jean Isaacs choreographed “Red Parasols,” in which Stevinson-Nollet dances amid eight onstage parasols. Angularly, with jutting hips and deep pliés, she seems to be hunting for a way out, as menacing man in a black shirt, pants, and bowler hat (Matt Carney) stalks her and sets the parasols into clattering spins. When the piece concludes with Stevinson-Nollet warily taking a parasol from Carney, it feels creepy. And confusing. The program states that red parasols are a symbol for the disruption of worldwide sex trafficking, and a little research reveals that they’re associated with sex workers advocating for themselves. Yet Stevinson-Nollet hardly seems empowered. Maybe Isaacs was going for ambiguity, but this piece felt as if it needed to be more thought through.

Expressive arms and a mobile torso mark “Slip Face” by Kate Weare. Stevinson-Nollet, in a red dress, floats her arms to one side like a hula dancer, waves an arm as if opening a door, or turns with both arms pumping. She advances across the stage, then pulls back, in a cascade of movement so organic, there’s almost nothing about this piece in my notes. I was simply mesmerized. Talking to Stevinson-Nollet later, I found out that Weare was working with the image of sand moving on the face of dunes, and the dance felt like that.

“Je Ne Sais Quoi.” Photo: Jeff Teitler

Stevinson-Nollet closed with her own “Je Ne Sais Quoi,”a playful duet with bassist Robert Black. A founding member of the Bang on a Can All Stars, Black can make an acoustic bass rumble nervously, or whisper like a cat being stroked (the sound of the fur as you stroke it), or take on a nasal tone like an instrument from the Asian steppes; he also does a mean jazz pizzicato. He plays onstage (and barefoot), as Stevinson-Nollet rises and falls, seems blown backward, and runs in a circle. Then she and Black go into a standoff, in which the bass becomes a tool: he hides behind it or raises it like a weapon and runs at her. She grabs the bow and brandishes it, scampering like a mischievous kid.

And isn’t that how art gets created, with the exploratory spirit and sense of fun that children bring to play?

Sunday: “Light in Dark”

A question circulating in the audience on Sunday was, “How old is Christine Dakin?” because she moves with such authority and power, utterly holding the stage in two solos, yet she joined the Martha Graham Company in 1976, so she’s got to be … ?

Dakin is 68, and she’s a master, performing both a Graham classic and a piece choreographed for her last year.

Dakin in “Short Story.” Thanks to Janelle Freiman Orsi for catching this on her phone.

In “Short Story” (2017), by Mexican choreographer Jaime Blanc, Dakin seems a woman traversing her life. Sometimes she gets by on charm, with an ingratiating smile and mincing presence that made me think of Amanda in Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie” welcoming the gentleman caller (and that was before I read that this piece was inspired by a Williams story). But all the while, she’s screaming inside—reflected in howls and grunts in the score, Berio’s “Sequenza III” for voice, recorded by Cathy Berberian—and sometimes it comes out in a twisted cowering pose or a frantic, scurrying run.

The pièce de résistance—for Dakin and the Live Arts Fest—was “Canto Jondo” (Deep Song), Graham’s cry of anguish over the Spanish Civil War, which she created in 1937 and initially performed herself. Graham also designed the visually stunning costume, a dress with alternating vertical panels in black and white, a color palette inspired by Picasso’s painting in response to the war, “Guernica.”

Canto Jondo. Photo: Janelle Freiman Orsi.

Just seeing Dakin come out in the dress and sit on the one set element, a simple white bench, is a thrill. And it’s more thrilling when she moves—reaching, writhing, coming to her knees and leaning back with that powerful Graham pelvic contraction—as William Coulter performs his guitar arrangement of the Henry Cowell score.

Graham’s angst-laden aesthetic was pushed aside by postmodern dance, with good reason. But seeing Dakin in “Canto Jondo” is a reminder of the extraordinary art that Graham and her dancers made.

Also on Sunday, Lux Boreal did “Stravinsky Interpolations,” part of Stravinsky’s “Histoire du Soldat,” which the company performed in February with La Jolla Symphony and Chorus. Their version, created with La Jolla Symphony Director Steven Schick, departs from the traditional story—of a Russian soldier who makes a deal with the devil—and uses text from Luis Alberto Urrea’s “Tijuana Book of the Dead.”

Choreographed by Henry Torres Blanco, the dance features the compelling Briseida López as the person who yields to satanic temptation (at least, that’s how I read it), doing quick skipping turns and spinal undulations, and projecting vivid emotion. In partnering with powerhouse Ángel Arámbula, sometimes they’re like lovers, and sometimes they seem to be adversaries. When Raúl Navarro enters snakelike with sinuous arms, Lopez is both frightened and captivated.

A demonic trio—Matthew Armstrong, Melissa Padilla, and Victoria Reyes—flings themselves into wheeling turns in amazingly tight unison and circle López, tormenting her. And there’s a beautiful bit with pouring sand from a pitcher into dancers’ hands.

It’s chancy to present a truncated version of a full production, and, although I could watch these dancers do anything, this piece felt incomplete. Obviously, they couldn’t provide live music or higher-tech lighting. But, because the piece is so narrative, I wish they had done a synopsis of the story in the program—a reader (uncredited) read sections, some in Spanish and some in English, but he was difficult to follow.

Award-winning dance journalist Janice Steinberg has published more than 400 articles in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Dance Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. She was a 2004 New York Times-National Endowment for the Arts fellow at the Institute for Dance Criticism and has taught dance criticism at San Diego State University. She is also a novelist, author of The Tin Horse (Random House, 2013). For why she’s passionate about dance, see this article on her web site, The Tin Horse

the most amazing dance fest I’ve ever seen! So much for so little in such a short time – 10 days!