Music is the Lifeblood, Malashock’s Choreography Adds Stunning Physicality

The title of Malashock Dance’s new show, “Lifeblood Harmony,” reflects John Malashock’s belief that “Music is the lifeblood of dance.” For this program of three premieres, which runs through Saturday, Malashock found an ideal collaborator in violinist Kate Hatmaker, Artistic Director of the innovative chamber ensemble Art of Elan. They chose a rich and varied palette of contemporary classical work – by Judd Greenstein, Osvaldo Golijov, and David Bruce – for Art of Elan to perform onstage.

The title of Malashock Dance’s new show, “Lifeblood Harmony,” reflects John Malashock’s belief that “Music is the lifeblood of dance.” For this program of three premieres, which runs through Saturday, Malashock found an ideal collaborator in violinist Kate Hatmaker, Artistic Director of the innovative chamber ensemble Art of Elan. They chose a rich and varied palette of contemporary classical work – by Judd Greenstein, Osvaldo Golijov, and David Bruce – for Art of Elan to perform onstage.

The live music, a rarity for dance, is one of the delights of this show. So is the full-scale staging possible at the Mandell Weiss Theatre, in which Jennifer Setlow’s lighting makes the dancers’ skin glow. And if music is the lifeblood, Malashock’s choreography adds bones, muscles, and powerful visual imagery. From the lilting playfulness of the opening “Great Day” to a final image of transcendence, “Lifeblood Harmony” is a thrilling evening of dance.

In “Great Day,” to “At the End of a Really Great Day” by Greenstein, two men and three women are like kids at play. To light pizzicato strings, Spencer Ramirez and Justin Viernes come at each other in friendly chest-bumps. Stephanie Harvey, a fearless sprite, flings herself into space, the men catch her, and she does the splits in the air. There are pony-like prances and games of crack the whip, and, throughout, a sense of suspension, every ascending movement lingering at its highest point, as if Elisa Benzoni’s summery white costumes – bell-like skirts and loose-legged pants – contained anti-gravity dust.

Heather Glabe separates from the other dancers both physically and by doing a surprisingly mimetic move, as if she’s stirring a pot and then tasting. Later, the others pair up, and Glabe is in a corner, her back to us, as she grooves with the musicians – and it’s a reminder of the story behind this composition: a young friend of Greenstein’s died suddenly in an accident, and someone remarked, “She died at the end of a really great day.”

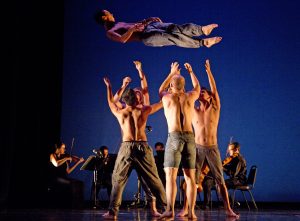

So maybe Glabe represents the woman who died, though any hints of narrative are done with impeccable subtlety. That’s the case with “Dreams & Prayers,” as well. “Dreams & Prayers” is set to Golijov’s “The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind.” Isaac the Blind was a medieval Jewish mystic, and a clarinet (played by John Klinghammer) weaves klezmer phrases through the haunting score. There are times when Viernes seems the central Isaac character, for instance when he’s held upside-down like the Hanged Man in the Tarot. But sometimes Harvey is at the center of the group, particularly in a breathtaking image: arms and legs splayed à la da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, she’s held aloft and her entire body rotated in quarter turns.

And story is far less important here than the otherworldly mood and electrifying sculptural imagery, which also includes a head “sandwich”: one of the seven dancers lies with her head on the floor, the next places his head directly above hers but from the other direction, and so on. There’s also a wonderful move, in which, arms held in tightly to the body, the dancer jumps at an angle and keeps everything in a straight line.

(A word about the dancers: The standouts in this program are the quicksilver Harvey and Viernes, who shows more authority and emotional depth every time I see him. But everyone in the company is strong, and what a pleasure to see Ramirez, a powerful veteran of Mark Morris’s company, as a guest artist.)

The story behind “Gumboots” – to David Bruce’s piece of that title – involves the shameful history of native Africans in shackles working colonists’ diamond mines. Using the gumboots they wore in the damp mines, they created an exuberant style of dance. A similar transformation from spirit-deadening slavery to joyous self-expression makes “Gumboots” the most narrative of these dances.

The story behind “Gumboots” – to David Bruce’s piece of that title – involves the shameful history of native Africans in shackles working colonists’ diamond mines. Using the gumboots they wore in the damp mines, they created an exuberant style of dance. A similar transformation from spirit-deadening slavery to joyous self-expression makes “Gumboots” the most narrative of these dances.

There’s a suggestion of shackles as dancers enter in five male-female pairs, arms held in front of them with elbows bent and lower arms locked together. Proceeding at a heavy trudge, the men come to the floor and lie as if lifeless, as the women form their own circle of support. Then, in a touch that feels Shakespearean, all freeze as if under an enchantment, and, to a blithe violin, a spirit – Harvey – darts among them, conjuring them back to life.

It takes time. There are more shackled arms, and at one point the dancers stay offstage and we have only the musicians playing a movement that sounds like spring returning and birdies singing. But gradually we get playful moves and flirtation, the men showing off by standing on their hands and kicking their feet in the air. In a play on folk dance, everyone does big-armed leaps through a basket-weave line.

“Gumboots” ends with Harvey being tossed exultantly into the air. It’s a Paul Taylor moment, and, like Taylor’s dances, this work could hold its own on an international stage. Given the logistics of touring musicians as well as dancers, that may never happen. So be warned: This brief run may be your only chance to see “Lifeblood Harmony” as Malashock and Hatmaker envisioned it. Do not miss it.

7:30 tonight and tomorrow night, Mandell Weiss Theatre, UCSD

Award-winning dance journalist Janice Steinberg has published more than 400 articles in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Dance Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. She was a 2004 New York Times-National Endowment for the Arts fellow at the Institute for Dance Criticism and has taught dance criticism at San Diego State University. She is also a novelist, author of The Tin Horse (Random House, 2013). For why she’s passionate about dance, see this article on her web site, The Tin Horse