Hershey Bars: Felder Shines in Mildly One-Sided ‘Maestro’

If dizzying migraines wouldn’t get Austrian composer and artistic director Gustav Mahler, tonsillitis would. Mahler died in 1911 at age 50 apparently from complications of the disease, his personal life dotted with bouts of rheumatic fever, a family history of mental illness and a bike accident that should have bought him the farm. The mishap occurred in 1896, four years after the Vienna Philharmonic’s debut of his absolutely magnificent “Resurrection” symphony, which he conducted as one of his blinding headaches raged unabated for two days on either side of the performance.

American icon Leonard Bernstein often spoke reverently of Mahler’s music, if longtime San Diego fave Hershey Felder’s nod to the legendary composer, conductor, pianist, teacher, writer and TV star is to be believed. Hershey Felder as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro, the current entry at San Diego Repertory Theatre, features several Bernstein idols in the same light, with writer/performer Felder (late of La Jolla and Point Loma) delivering a perfectly fine collage of musicianship, lecture and sketch comedy as his Bernstein ponders the nature of music and its synonymity with love itself.

Mahler, Ludwig van Beethoven, Richard Wagner, Aaron Copland, conductor Serge Koussevitzky and relatively unknown radio man Tom Cothran never get quite enough expository play for us to call this a full-throated anecdote, but they do fill this Bernstein with answers amid his urgent search and, just as critically, fresh questions to fuel his obsessions on music’s place in the human experience.

Eyes front — or else — as Leonard Bernstein (Hershey Felder) is master of all he surveys. Photo by Michael Lamont.

Bernstein was born in 1918 in Lawrence, Mass., to polar-opposite Ukrainian-Jewish parents — father Sam, owner of a hairdresser supplies franchise, was a stick-in-the-mud critic of his son’s interest in music (“Get a real job,” he’d intone in a precious Yiddish accent), while fun-loving mom Jennie was always up for rabble-rousing with Lenny, his brother Burt and his sister Shirley Anne. Everything came out in the wash, as Sam eventually bought Len his first grand piano.

From there was launched a colossal musical ambassadorship, with Bernstein at the center of the nation’s regard for classical taste (for starters, he’d pen three symphonies and write the music for the incomparable West Side Story; he hosted CBS-TV’s Young People’s Concerts for 14 years and conducted The New York Philharmonic for a decade ending in 1969; and he wrote or contributed to 23 books, one ironically titled I Hate Music, that helped solidify his place as this country’s go-to star in virtually all matters musical). Hard to believe he was only 72 when he died (New York, 1990, heart attack) — such was the household presence of a musical envoy we haven’t known before or since.

The show suffers mildly from Bernsteinitis…

Still, and counterintuitively, this show overflows with family and professional recollections almost to a fault. While Mahler’s crippling headaches and bike accident may have nearly altered the course of music history, they were nothing compared with his mother fixation (as diagnosed by none other than Sigmund Freud) or the abuse he suffered at his father Bernard’s hands. Indeed, his colossal egotism earned him a clutch of full-blown enemies, regarded by his supporters as devils incarnate.

You’ll never hear anything about that in this show. Any more than you’ll get a glimpse of Wagner’s hard-won marriage to Cosima, daughter of Hungarian composer Franz Liszt. Or Copland’s federal blacklisting during the red scare of the 1950s. Or that Beethoven’s deafness might have been caused by his propensity for sticking his head in a bucket of cold water to keep himself awake. Or of Bernstein’s affection for the music of the Beatles as well as such diverse acts as the Association, the Byrds and the Kinks. The show suffers mildly from Bernsteinitis, wherein we learn everything about Lenny’s music and too little on the human attributes of the composers who so greatly influenced him. His icons, after all, are subject to the same physical laws as you, I and, indeed, Bernstein himself.

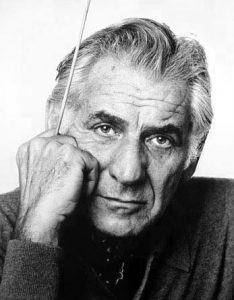

A life of angst and joy is reflected amid Leonard Bernstein’s grizzled, eminently familiar countenance. Public domain photo

There’s also something unsettlingly youthful about Felder’s looks. While he sports Lenny’s more handsome traits, he lacks the sinew and sunkenness in a face riddled with life’s angst and joys. Bernstein’s bisexuality, for example, led him to leave his wife Felicia Montealegre for radio music director Cothern in 1976 — two years later, Felicia died of cancer, and Bernstein, a father of three, suffered enormous, paralyzing guilt over her death. Felder, by contrast, looks absolutely none the worse for wear in every context, including a prolonged flap over a 1960s benefit he held for the Black Panther Party (race and its parallels with modern music were a favorite topic).

But Felder has an excellent handle on the depth of character arc in one so esteemed and self-styled. “I am God!” his character declares (and means it) amid unparalleled adulation; only a few minutes before, he was shticking on Copland’s squealy voice and Sam’s hopelessly conservative values. Add Felder’s savvy pianism amid Francois-Pierre Couture’s properly threadbare set and Christopher Ash’s judicious facial projections, and this Joel Zwick-helmed biography snatches Bernstein out of midair, his well-worn legacy intact.

Case in point: Felder is the husband of Avril (Kim) Campbell, who in 1993 served as Progressive Conservative prime minister of Canada. In losing her post to the Liberals in the 1993 election, Campbell quipped, “Gee; I’m glad I didn’t sell my car.” Unadulterated, vintage Bernstein.

This review is based on the opening-night performance of July 7. Maestro runs through July 17 at San Diego Repertory Theatre, 79 Horton Plaza downtown. $60-$89. sdrep.org, (619) 544-1000.

Martin Jones Westlin, principal at editorial consultancy Words Are Not Enough and La Jolla Village News editor emeritus, has been a theater critic and editor/writer for 25 of his 47 years…

More…