‘Hamilton’ Is About More Than Just One Revolution; Make Room for Miranda

If we truly are nearing the end of the Founding-Fathers-As-Gods Era in American history, then Lin-Manuel Miranda’s majestical musical drama Hamilton can be seen as both a gravestone and a signpost.

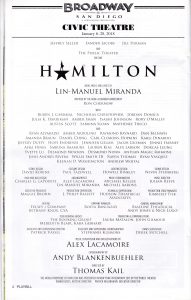

The landmark show, now in a three-week engagement at the Civic Theatre, is a vernacular masterpiece of interpreting history, at once emotionally overwhelming and mentally stimulating. Its particular genius is the way Miranda ignores the trivia of reality to bear down on the core of truth.

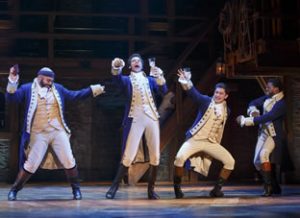

The artists onstage represent not the handful of European colonists who conceived of and gave birth to this unique country but the far broader spectrum of citizens who have sustained it. Verisimilitude in theatre presentation is over-rated anyway.

Alexander Hamilton has always been one of the least understood Founders. He didn’t sign the Declaration of Independence, he never got elected president and he was best-known for being killed in a duel by one Aaron Burr, who was otherwise unknown. Next to George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, these guys were nobodies.

Yet both Burr and Hamilton were fascinating, complex characters, like dozens of others who somehow landed together in time and space to pull off one of history’s most astounding feats of governing politics.

Generations of Americans have grown up soaked in the passions of the Revolution; only gradually have detached historians begun to construct the true structure of the story which, as so often happens, is far more fascinating and inspiring than the myths. It was Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton that really re-introduced the man to the world and eventually inspired Miranda’s interest.

And why not? Unlike the aristocratic, professional and mercantile white men who dominated the country’s early leadership, Hamilton was a bastard born in poverty on the Caribbean island of Nevis, sent by local leaders to New York for an education. Ultimately he would serve as General Washington’s indispensable aide. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, he introduced financial order, established a national bank and founded the U.S. Coast Guard. He was an attorney, the founder of the New York Post and the principal author of The Federal Papers interpreting the Constitution. His vision of a strong federal government and an economy based on industry and commerce was strongly opposed by the southern slave-holding states led by Jefferson, who favored states’ rights in an agrarian paradise.

An immigrant with a dismal past, then, who survived and flourished at the highest levels only through merit. An ideal messenger to reexamine the past with a more inclusive, egalitarian approach using a contemporary theatrical vocabulary rooted in street smarts and pop entertainment, wielded by a theatre genius comfortable with these tools and all the others.

Miranda, of Puerto Rican ancestry, had a major Broadway success soon after graduating from Wesleyan University with In the Heights (2008) as songwriter and leading actor. It was that year that he discovered Chernow’s book and wrote a rap that became part of the Hamilton score and attracted attention from the White House to the New York Shakespeare Festival where Hamilton premiered in 2015, on the same stage where, 40 years earlier, A Chorus Line was introduced.

When transferred to Broadway, the show won just about every award available and settled in as the hottest ticket in decades, with some seats selling at the box office for over $1,000 (and others going at vastly cut rates to students).

Performed by a resolutely mixed cast of 21 and an orchestra of 10, including a string quartet, the show is a dizzy mixture of styles and influences including hip-rock, rock, pop, jazz and salsa but also nuggets from the Broadway heritage (South Pacific gets quoted) and even Gilbert and Sullivan.

Miranda’s book is a rigorously selective narrative boiled down to 150 minutes from Chernow’s 600+ pages and sung, chanted and danced with scarcely a pause. Even vastly complex characters get squeezed into memes – Thomas Jefferson is a simpering schemer – and nobody is allowed much rumination.

But the power and the heft of the piece are overwhelming. These are artists totally convinced by their work and reluctant to let anybody depart unconverted. And this is art of rare substance.

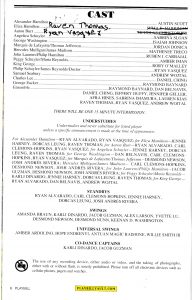

Presently, there are four companies of Hamilton on view: Broadway, London, Chicago and this one, the first national company, late in residence at San Francisco and Los Angeles. As the serious touring grind begins, there has been turnover in the cast. Printed updates are inserted into each program and no publicity photos of this cast are yet available.

But I suspect it doesn’t matter much. Austin Scott in the title role transfixed me sufficiently. Ryan Vasquez is wrestling yet with the enigma of Miranda’s Burr. And the featured women –Raven Thomas as Hamilton’s wife, Sabrina Sloan as his sister-in-law and Amber Iman as his predatory lover – all could be more vivid. Only Rory O’Malley’s mildly curious King George III seems complete, within this context.

And there is such a bothersome lack in the sound system, all-important where the words are so essential, that I pondered suggesting projected dialogue a la opera. But, as was rightfully pointed out to me, the eyes mustn’t be dragged away from this vision even for a moment.

Director Thomas Kail has found a muscular, aggressive pace for the show, based on the signature pose of the hero, feet apart, back shoulder dropped and finger jabbed at the heavens, that commands close attention. Kail, and choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler, have packed it all together with precise detail casually tossed past the inattentive, rewarding concentration that in turn screws tighter the show’s tension.

That pose is underlined by stabs of hard-edged spotlights, ripping the candle-lit levels in Howell Binkley’s lighting to stark effect. Paul Tazewell’s costumes for the principals resemble paintings of the period whereas the company’s basic look is corsets for the ladies and muscle shirts for the men, with resulting flexibility and a frisson of sexuality. David Korins’ soaring scenery is crude wood and bricks with tricks as needed.

There is more than one Revolution at work here. Miranda is serving notice on the theatre than a new generation has arrived, bringing with it a meritocracy that allows art room to bloom.

And Chernow may not have it all right. (For one conflicting opinion on the protagonists, see Gore Vidal’s 1973 novel, Burr.) But the impact of the facts he has so patiently gathered makes it a story well worth more investigation, by historians and artists too.

(Continues at 7 p.m. Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 7:30 p.m. Thursdays, 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, 2 p.m. Saturdays and 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays through Jan. 28, 2018.)

Welton Jones has been following entertainment and the arts around for years, writing about them. Thirty-five of those years were spent at the UNION-TRIBUNE, the last decade was with SANDIEGO.COM.