Even Genocide Can’t Stop the Rock ‘n’ Roll In Cambodia

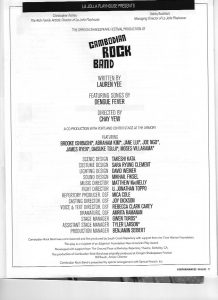

If you’re going to write a play about a place and a people and a culture unfamiliar to your audience, it’s not a bad idea to include a rock ‘n’ roll band in the show. Even maybe dangle the pop promise in the title, like Lauren Yee has done with Cambodian Rock Band, now at the La Jolla Playhouse.

The story is a somber reflection on the horrendous genocide of the country’s civil war during the imperialistic hangover of the 1970s when at least a quarter of the Cambodian population was slaughtered, usually with unspeakable cruelties, for being corrupt aristocrats. (One dead giveaway of status: Wearing glasses.) That included an estimated 90 percent of the country’s artists, wreaking havoc with classical artistic traditions passed on verbally for centuries.

Thanks to the slop-over from the period’s endless Vietnamese wars next door, there also was a lively Western-flavored pop music scene in Cambodia. When the nightmare descended, the rockers were at least as vulnerable as all other performers. But some recordings survived and restoration is underway. Yee’s play relates the process.

It’s hard to picture a culture as abused as the Cambodians were. A 1985 production in Paris by Ariane Mnouchkine’s Theatre de Soleil of Helene Cixcus’ play The Terrible but Unended Story of Norodom, Sihanouk, King of Cambodia took nine hours over two separate performances of Shakespearean scope and majesty to scratch the surface. I remember several specific actors and an enormous arena stage (the Cartoucherie de Vincennes) ringed by 600 statues of Cambodians and others, gravely and silently observing the action. But I don’t remember anything about rock ‘n’ roll.

Joe Ngo, Brooke Ishibashi and Moses Villarama, left to right, are the front line of the Cambodian Rock Band at the La Jolla Playhouse. Jim Carmody Photo

From this detail, though, Yee has fashioned a surprisingly effective evocation of an era now receding as the next waves of vivid history lash the world’s collective conscience. Reunion and restoration continue to heal with time and there’s value in comfortable links. The band that opens the show – lead singer, guitar, bass, keyboards and drums – plays a reasonably solid set of songs salvaged from the ‘60s and early ‘70s plus some pieces from Dengue Fever, a Los Angeles band inspired by the Cambodian mixture of that golden age. Yee credits that band with inspiring her to begin work on this play.

It’s a sincere play, a story of survivors’ burdens and inheritors’ puzzlement. The music helps a lot. This production, imported from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, doesn’t.

Five of the six cast-members form the band; three of them shoulder acting loads. As always with such arrangements, somebody must face the question of whether it’s best to hire actors and hope they can learn to play the music or vice versa. In this case, the compromises are solid. The music does its job and most problems with the acting are the result of poor artistic decisions.

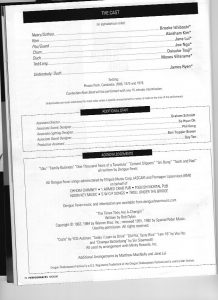

Abraham Kim does fine as the doofus drummer and Jane Lui, who shares credit with Matthew Mac Nelly for the arrangements, plays keyboard and a couple of small roles with solid conviction. Moses Villarama is a plausible bassist and juvenile lead, with some tension available for a desperate prisoner and Brooke Ishibashi sings energetically with the band and represents the present generation well enough.

The menace is represented by the formidable James Ryen, who towers over the rest of the cast like a basketball star in the jockey room. His role, drawn at least partly from an actual historic boss from the nightmare years, is complex in an annoying fashion and really doesn’t help explain the acid chaos of the time. He’s listed in the program as an understudy but that’s not the problem. He makes the role his and does what he can.

Joe Ngo, left, in Lauren Yee’s play Cambodian Rock Band at the La Jolla Playhouse with, right to left, Moses Villarama, Abraham Kim, Jane Lui and Brooke Ishibashi. Jim Carmody photo

What the play is all about, though, is the Everyman character of Chum, lead guitar in the band and one of the very few left to tell the story. Joe Ngo, a wiry whirlwind of presence with comic thrust and urgent hysteria readily at hand, simply pounds his role into a paste without any connective illumination. He plays that guitar like a tiger but his acting is more in the hyena line.

That has to be at least partly due to the decisions of director Chay Yew, who misses numerous opportunities to grout together words and music and emotions.

Takeshi Kata’s set is sturdy and versatile, Sara Ryung Clement’s costumes seem right and David Weiner sorts out periods with confident lighting.

(Continues in the La Jolla Playhouse’s Potiker Theatre at UCSD Tuesdays and Wednesdays at 7:30 p.m.; Thursdays-Saturdays at 8 p.m.; Saturdays and Sundays at 2 p.m.; and Sundays at 7 p.m. through Dec. 15, 2019.)

Welton Jones has been following entertainment and the arts around for years, writing about them. Thirty-five of those years were spent at the UNION-TRIBUNE, the last decade was with SANDIEGO.COM.