A.I.M Offers a Bonus: A Performance by Kyle Abraham

Photo: Steven Schreiber

Kyle Abraham took us in his arms and invited us in with three intimate pieces danced by his superb A.I.M (Abraham.In.Motion) company at the Balboa Theatre on Thursday. Then, before anyone could get too comfortable, he ignited the stage with the propulsive, hip hop-flavored “Drive.”

The program, presented by UCSD ArtPower didn’t just showcase the New York dance maker’s range, it offered a rare treat: Abraham himself, filling in—in “The Quiet Dance”—for a company member who couldn’t perform that night.

Abraham has been in the limelight for over a decade. He was one of Dance Magazine’s “25 to Watch” in 2009 and won a Bessie Award the next year. In 2013, he received a MacArthur Foundation award. But this was his company’s first San Diego performance, and part of the pre-show buzz was seeing how many local dance artists were in the audience.

Along with “The Quiet Dance,” the program included “Meditation: A Silent Prayer” and an excerpt from “Dearest Home” that was performed in silence. It was astonishing how quiet yet compelling Abraham’s work can be.

Tamisha Guy in “Dearest Home.” In the excerpt done here, she wore jeans and a casual shirt. Photo: Carrie Schneider

In “Dearest Home” (2017), silence heightens the tension between Tamisha Guy and Jae Neal, who seem to yearn to connect but fear getting too close. Standing at a wary distance, they are keenly aware of each other, doing delicate hand gestures and pirouettes in unison. They break into their own dances, asserting their individuality by lunging and arching with gorgeous balletic lines. (That’s balletic as in William Forsythe’s style, movement impulses flowing through their bodies.) Occasionally, they touch—but shyly, Guy putting a hand on Neal’s leg, then backing off. She even shoves Neal, who doesn’t fight back but gives her space.

Dan Scully’s low, behind-the-dancers lighting heightens the sense of intimacy in this history-of-a-relationship duet. Scully, a New York-based designer, designed all of the lighting, and it brilliantly reflects the mood of each piece.

“The Quiet Dance” begins in silence, with Abraham standing alone, his fluid arms swimming through the air. Four dancers join him, and there’s music, Leonard Bernstein’s “Some Other Time” in a contemplative instrumental recording by pianist Bill Evans. My eyes are drawn to the dancers’ hearts, as they fold their hands into their chests or go into big lunges, arms thrown back. As in “Dearest Home,” people connect—there’s a delicious unison move, one knee swiveling while the arms form a rocking cradle—but they rarely touch. Yet it doesn’t feel as if they’re avoiding one another; rather, there’s a gentleness and a lovely sense of restraint.

Photo: Steven Schreiber

Abraham asked two fellow MacArthur winners, Titus Kaphar and Carrie Mae Weems, to collaborate on “Meditation: A Silent Prayer.” Kaphar created white-on-black asphalt and chalk drawings of enormous, sorrowful faces that hang behind the dancers. What initially looks like three faces morphs, with changes in the lighting, into nine; each image has three layers, depicting nine people killed by police. Multi-media artist Weems wrote and recorded a text about police violence against African-Americans—“He was trying to get his ID out of his pocket. They shot his arm off.”—and a recitation of tragically familiar names: “Trayvon Martin. Eric Garner,” and the list goes on.

The meditative silence in this piece comes from the six dancers. Subdued and dimly-lit, they cluster together, roll on the floor, come to their knees. Those balletic arms reach to forever. As we hear the litany of victims, they simply stand and face the paintings. In fact, they’re a bit overshadowed by the powerful set and text. I had a sense of Abraham graciously stepping back and letting his collaborators shine. I wish he’d been more assertive with the dance.

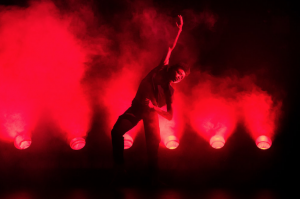

There’s plenty of assertiveness in the high-octane “Drive”—and plenty of sound. To urgent percussion and an insistent voice repeating, “Where’s your drive?” (Theo Parrish’s “Drive”), eight dancers scramble with powerhouse leg swings, sharp isolations, slashing arms. One minute, they’re doing unison pirouettes, the next owning the stage in dance-battle solos.

Photo: Ian Douglas

Scully’s lighting fit the pensiveness of the first three dances. In “Drive,” he lets loose. His rear lighting includes mid-level banks of bright white, a stunning blue diagonal, and steaming floor-level reds. It feels like a fireworks finale, and so does the dance.

This was a one-night-only performance. However, you can catch the next event in ArtPower’s excellent dance series, the British-based Rosie Kay Dance Company, at the White Box at Liberty Station March 4-7.

Award-winning dance journalist Janice Steinberg has published more than 400 articles in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Dance Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. She was a 2004 New York Times-National Endowment for the Arts fellow at the Institute for Dance Criticism and has taught dance criticism at San Diego State University. She is also a novelist, author of The Tin Horse (Random House, 2013). For why she’s passionate about dance, see this article on her web site, The Tin Horse