Being Alone: Paintings by James Chronister at Lux

Being alone while lost in a forest or feeling tiny in a vast space is a natural cause for melancholic apprehension. Not being in control, not being the master of the situation, being at the mercy of nature―or worse, being at the mercy of God himself―falls into the artistic tradition called the “Romantic Sublime.” The master artist from this tradition is early 19th-century German painter Caspar David Friedrich. San Francisco artist James Chronister offers viewers black and white paintings with the same feeling of sublime melancholic isolation in an exhibition now on view at the Lux Art Institute in Encinitas.

All of Chronister’s paintings are void of human life whether depicting forests or empty, imposing rooms from British grand manor houses. He bases his paintings on black and white photographs or lithographic images. He grids off the source image and then in a darkened room projects a grid onto his bare canvas. Then he laboriously proceeds to copy the image onto the larger canvas square by square applying tiny “V-shaped” brushstrokes.

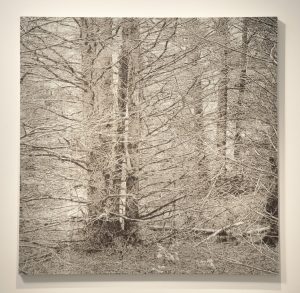

James Chronister’s “Untitled (Wildness),” 2009.

Oil on canvas; 60 x 60-inches.

Photo credit: © 2013 by Daniele Bini.

Chuck Close used a similar gridding technique to produce his fool-the-eye photo-realist paintings in the late 1960s. Alternately using a projector, in the 1960s and ’70s German artist Gerhard Richter copied photographs, too, but always acknowledged his works as paintings by blurring his paintings of photographic images with brushstrokes. Like Richter, rather than convince the viewer of their photographic exactness, Chronister instead uses the “V-shaped” strokes to firmly keep his work in the realm of painting rather than try to fool-the-eye with painted photographic illusions.

This exhibition offers two subjects. One subject draws on memories of lone walks in the forest near where he grew up in Helena, Montana. His earlier paintings depict forested nature. The most complex of his forest scenes is “Untitled (Wildness),” 2009. On an almost glass smooth white surface, a warm black matrix of tiny strokes depict a fall scene of a thick tangle of three leafless trees standing just to the right of the center of the square painting. Crowding in from the flanking foregrounds are more tangled webs of leafless limbs, and there are more and more leafless crowded, tangled trees and limbs that continue into the background. In the foreground is a solitary shrub’s cluster of white seed heads that become an analogy for the looming snow of winter.

Along with the isolation of the dense nature scene, Chronister also manages to infuse this painting with a sparse overall matrix of implied vertical and horizontal lines. This infusion of rectilinear lines into an isolated natural scene brings together a nexus of ideas from the Romantic Sublime and the ideals from 20th-century high Modernism. The modern ideals of Neo-plasticism reduced pictorial language into a base vocabulary of painted horizontal and vertical lines and painting such lines became an authentic religious ritual for artist Piet Mondrian. Also, Abstract Expressionist painter Barnett Newman created vertical lines called “zips” that he also believed to have both religious and sublime meanings.

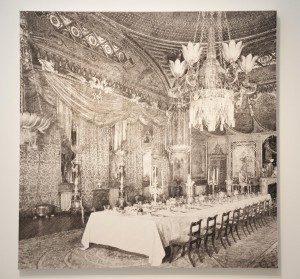

James Chronister’s “Brighton,” 2012.

Oil on Canvas; 60 x 60-inches.

Photo credit: © 2013 by Daniele Bini.

More recently, Chronister has been making paintings based on his remembrances of a trip to England. The source images are old period images of huge rooms from famous English manor houses. His painting “Brighton” (2012) features a slightly out of focus, image of the dining room from the Royal Pavilion designed by John Nash for George, Prince of Wales (the future George IV) at Brighton. The immense dining room features mammoth lotus blossom chandeliers under a wide dome. Visitors were supposed to feel small in comparison to the grandiose architecture akin to the feeling of isolation and fear of vast nature in the concept of the Romantic Sublime. Chronister’s approach to the subject is another coming together of image with ideas of isolation, but in this series the interior of a house invokes the same sense of discomfort. It is an unexpected and surprisingly effective sensation.

Other paintings in the series have titles such as “Devonshire” (2011), which refers to Devonshire House at Piccadilly, which was demolished in the 1920s. It was the London home of the powerful 5th Duke and famous Duchess of Devonshire in the late 1700s. As the home no longer exists, the painting refers to the idea of nostalgia, which is also a concept related to the Romantic Sublime.

Chronister’s paintings feature either nature’s purity or mammon. As he paints alone in the dark, is he not a virtual monk? Is he not painting from other sources? Does that make him a lone monk copying images? Perhaps he is illuminating documents that name our fears so we can again master them―to no longer be at their mercy. There is a strong unity to both his solitary method of painting and to the images he presents. Together with the universal feelings he conveys and the type of labor involved to produce his artwork make this exhibition worth a trip to Encinitas to view.

James Chronister is currently in residence at Lux producing a new painting in the dark behind a big black curtain in the gallery. The new artwork will be placed on display upon its scheduled completion on April 13th. The exhibition will continue through May 18th, 2013.

The exhibition runs March 14 through May 18th, 2013.

© 2013 by Kraig Cavanaugh

Kraig Cavanaugh lectures about art history—specializing in Modern & Contemporary Art—as well as being an instructor of color theory, design, and studio art. He has curated numerous art exhibitions, authored exhibition catalogues, and written art reviews for several other print and online journals including “Artweek” (USA) and “Selvedge” (UK) magazines. Cavanaugh is also an invited member of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art (United States division), which is an NGO in official relations with UNESCO.