A Pandemic Flip of Art and Audience

What makes live performance or live exhibition different is the immediacy of the experience. Watching someone play a concerto, recite a sonnet, enact a dramatic scene – even view a painting up close – has magic that pre-recorded versions do not. With pre-recorded concerts or plays or looking at photographs of a painting in a book, the observer sits a level away from the art – a diaphanous layer, like dirty eyeglasses, separates us from the present moment of creation, especially with live performance.

A not so far off future heads up display with concert information in a drive-in concert presented by Mainly Mozart.

But what makes the experience real for us? Separated from the live venue, we can’t hear the original sounds pulsing through the air or likely hear the foot falls of a dancer landing from a jete` or take in the original color of the strokes in a painting. We mimic all of that, trying to digitize it for later replay, but look at even the resurgence of vinyl recordings as closer to reproducing the authentic sound compared to the clean room version on a CD, DVD or digital file.

So, what do we do when we can’t go to the theater, watch a dance recital, listen to a live music performance or visit an art gallery? What opportunities does this time open? Rather than think in a straight line, let’s follow Hawthorne’s model for how history works, in a repeating spiral, covering new ground even while circling over the same old stuff.

In every big change, temporary or not, there is opportunity. The creative world is in a unique position to lead. If you believe, as I do, that art – or Art – is a natural and necessary part of living, springing from the spontaneous and the planned, then it’s important to look further than the traditional, tried and true.

In K-12 classrooms, there’s a concept called the “flipped” class. Instead of lectures from and presentations by the teachers and professors, the students work on their homework in class with assistance from the teachers. At home, they watch or listen to the presentation by the teacher. With all the changes contemplated while we remain 6 feet or more from each other, the arts community might consider flipping their presentations

How would that work?

First, of course, would be the consideration for the type of performance. Dance, painting and statuary lack a sound element, the quiet coughs at a dance recital and the shuffle of feet blended with the reverberations of murmured chatter in an art gallery, notwithstanding. That limits the delivery methods. Plays, music and speech can all be both visual and auditory that can be encoded to transmit in real time to our eyeballs and ears who then encode it for the brain.

Next would be to probe new ways to replace the intimacy of being physically present in the concert hall, theater or gallery. As live performance is not only the performance on the stage but the hum of an audience going in, sitting enrapt, applauding (or not) and the hubbub leaving.

If we focus on the full range of what makes art Art, the clues start to emerge for how we can continue to enjoy the elements of live performance without spending the effort to buy tickets, get dressed, drive distances, get home late at night and suffer the elbows, coughs and bad manners of large collections of people in a compressed space.

The “flipped” part comes into play by altering the timing and progress of a performance. Instead of counting on home study and experience to inform a listener or observer, weave the commentary, collect the reactions from the audience in real time. If the live performance must be mechanized to distribute, why not the banquet around it. Imagine attending one of Mainly Mozart’s live drive-in performances at the Del Mar Fairgrounds – delivered to a parking lot of cars over electronic means – and the heads-up display or tablet propped on teh dash in your car normally displaying speedometer and fuel, instead streams images of the composer and camera angles isolated on a particular performer from quiet drone out of ear shot but able to zoom the visual. At the break, you scroll back to show a companion just where your emotions were lit by the performance.

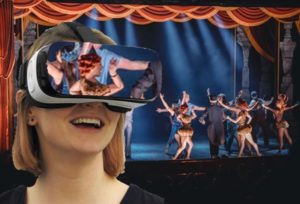

A woman enjoys a performance from home in a way she could not in person at the concert hall.

The key – the driver of live performance – is to induce immediacy, to close proximity. It’s interesting, this much bandied about term “virtual.” Its general meaning seems to be “not real because you’re not in the same physical space as the performers.” Just because we’re not present in the hall exposing rods and cones in the back of the eye to send electrical signals via the optic nerve to the brain doesn’t mean we’re not already “virtual” when we are in seat B12 next to the guy who keeps coughing during dramatic pauses.

The difference – the enhanced beyond human perception of reality possible with a new means of producing live performance, takes advantage of technology and its different management of time and space.

How much more engaging would it be to be able to split a screen between a wide view of a dance recital performed in the shallows of a lake and each dancer’s point of view as they reach toward each other. How much more could a choreographer express when that’s part of the physical poem.

And let’s be real about live performance. It shares what makes the Daytona 500 spectacular: the ever present possibility of a mistake, a slip in a performance that wasn’t there in rehearsal or last night and won’t be there tomorrow. In some ways that’s part of the treasure of live performance. With today’s technologies, there isn’t the same reason to record, edit and broadcast a performance thereby taking some of the joy out of it. And with vision enhancing tech becoming generally available, the small screen complaint can be dispensed with.

I’ve always thought the NFL is missing a huge rebroadcast opportunity. The size, speed and agility of the 22 players on the field lacks perspective. Take any game, then position civilians as an overlay on the action. Where Tyreek Hill of the Kansas City Chiefs starts on the 15 yard line to break right in a pass pattern on the 45, the desk worker civilian is just crossing the 25 in the same elapsed time. With the new “instruments” we have, we have an opportunity to deliver perspective in a new way.

We hear the best players from orchestras all over the country play together at a Mainly Mozart concert and it sounds perfect. Our sandiegostory.com classical music critic Ken Herman can detect a flat intonation of the second violins perhaps, but 99% of the audience missed it, or possibly weren’t as moved as they might have been but don’t know why. Today’s technologies can deliver those moments, at least to the extent the human brain can decode them. The opportunity comes from the other things we can do. The ability to quickly replay, to subtitle, to compare, to actually shift a point of view to seat among the second violins to better feel the direction coming from the conductor.

With my mobile phone (screen discretely held and dimmed of course), I like to use the SoundHound app. It listens to music and then uses the math of what it recorded to match patterns in a music library. I’ve had it find a performance by the San Diego Symphony pull up the same piece done by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Returning home, I can listen to that match and compare and discover new things about the piece I hadn’t noticed before. I’ve also had an orchestral performance of something by Bach pull up a rock anthem that fused the same phrasing.

Peter Schickele’s PDQ Bach presented Beethoven’s 5th but with play-by-play and color announcers like a football game on tv, addressing the issue of a dark concert hall and printed programs describing the piece to perform that most people don’t have time to read before the lights dim. That kind of lateral thinking – as clumsy as that example is – could stimulate other ways to bring the immediacy, intimacy and joy from a live performance during a pandemic.

To take advantage of studio quality sound, why not broadcast a performance from a sound stage or studio with socially distanced performers. Use the same setting movie producers use to match music to action – very like what the Symphony does on movie night or Mainly Mozart did one year with Peter and The Wolf – but with a new “artist” rehearsed and directed by the conductor: drone cameras and microphones moving through the artists isolating sounds and bringing focus as the conductor wishes. Most tv news broadcasts don’t employ camera operators on the same floor as the news readers. Robotic cameras move around in a ballet of technology taking instruction from a control room.

And the new audiences could be very large. The audience – all with a virtual headset on or in a small private theater with 3d capability – up close and personal and able to choose which stream to follow – switching at will. That solves another problem for live broadcast performances or even sports where the camera is one point of view for everyone. If you happen to want to focus on the bass fiddles and the director of the broadcast is, instead, scanning the front row of the first violins, you don’t have that choice you would have sitting in the hall. Why not provide the same with a live broadcast?

In the end, our technologies are advanced, but not yet to the point where the vibrations of the oboe reed can be perfectly replicated and sent over larger distances than the original sound waves from beside the French horn out to the audience in the concert hall. But there exists potential to grow audiences larger than fit in a single hall or gallery using the tech that we do have today to impart the joys of live performance. Now is a great time to explore those – and – when we can get back to making dinner reservations to stroll to the Old Globe for a play – we’ll have more choices and likely a larger number of total “ticket” buyers to fund the Arts.

With a Creative Writing degree from the University of Arizona and an MBA from the University of San Diego and years of website experience, Mr. Burgess supports this site with technical and publishing expertise and pretty much really enjoys working with everyone associated with it. Read more…