Sherlock Holmes Watches the Quick Changes With Admiration

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes floats majestically above an endlessly writhing tangle of adaptations, literature’s greatest sleuth, the gorilla in the room – copied, debunked but never ignored – for every crime-adventure story of the past century.

When Euan Morton, playing the immortal deducer in Ken Ludwig’s Baskerville: A Sherlock Holmes Mystery now at the Old Globe Theatre, whips out his large magnifying glass to get a better look at a clue, there’s an audible sigh and chuckle from the audience: We’re on familiar and beloved ground.

Euan Morton (foreground) with (from left) Andrew Kober, Liz Wisan and Usman Ally in Ken Ludwig’s Baskerville: A Sherlock Holmes Mystery at the Old Globe Theatre. Jim Cox Photo.

So it doesn’t really matter that this summer trifle soon pushes past the slobbering hound on the moors to become a clever exhibition of quick-change stagecraft. If we don’t know this particular story, we all know who’s going to win. And, more or less, how.

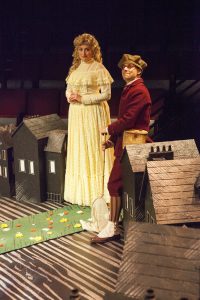

Morton plays Holmes in the grand tradition of brusque, impatient genius but he’s miscast. Too genial, too comfortable and too short. Usman Ally, his Dr. Watson, a foot taller and lean as a whippet, is as adoring, intense and supportive as tradition requires, but the show might have been more interesting if these actors switched roles.

Morton and Ally hold fast to their parts as the tale gallops from Victorian London to the gloomy Devonshire moors, but everybody else – man, woman and child – is played by one of three busy actors, Andrew Kober, Blake Segal or Liz Wisan.

This isn’t a new record. Google tells of a successful 2007 English version that used just three actors. But five is much better, as director Josh Rhodes amply demonstrates. Thus, our stalwart heroes are solid rocks in the rushing flood of characters: doctors, thugs, cab drivers, minor nobility, servants, nurses, neighbors, clerks, the dear landlady Mrs. Hudson, the stolid Scotland Yard Inspector Lestrade and even a couple of urchins from the Blake Street Irregulars.

Often the identity switches are astounding in their brisk efficiency. Only occasionally does a bit of Shirley Pierson’s rich period duds protrude from beneath another. And only once or twice does a scene require more than five voices, requiring some suspension of belief involving hats.

Blake Segal, Usman Ally and Euan Morton in Baskerville: A Sherlock Holmes Mystery at the Old Globe. Jim Cox Photo.

Rhodes’ staging makes use of his primary gig as a choreographer but not so much that one notices any gamboling. The ease of the transformations and the serene assurance of each succeeding character is a testament to the movement sense of both actors and directors. Even the dressers earn bows.

The designers all are on board, too. Wilson Chin’s set drips with Victorian clutter – a 70-year collection of chandeliers from the Globe warehouse inspires awe – but stays out of the way, around the perimeter of the Globe’s White Stage, where a row of cottages can suddenly become a table set for tea, without obstructing actor paths.

Austin B. Smith hustles the lighting precisely on cue and Bart Fasbender makes like the mad scientist with the sound: distant thunder, squeaking doors, wisps of music concocted for the occasion and, naturally, those hair-raising howls.

I can’t miss this opportunity to, once again, remind Conan Doyle fans that the original, authorized stage version of the character was written here, at the Hotel Del Coronado, over the Christmas holidays in 1889.

William Gillette, the immensely popular American actor-playwright, had persuaded Conan Doyle to give him the Holmes rights and he was working on the script during a West Coast tour of his Secret Service when the Baldwin Theatre in San Francisco burned down with all his scenery – and the unfinished manuscript.

Two weeks later, Gillette brought the troupe to San Diego for a single performance of Secret Service at the Fisher Opera House, and then dismissed the company. He stayed at the Del into the New Year and finished writing the script of Sherlock Holmes before returning home to Hartford, Conn. On Nov. 6, 1899, he opened the show on Broadway.

Gillette continued to turn the work into the 1930s when, during a farewell appearance at the Savoy Theatre in San Diego, he told this story to a reporter.

Oh, and what else? Nigel Bruce, who played Dr. Watson in the 14 films starring Basil Rathbone made from 1939 to 1946, was born in 1895 at Ensenada.

Continues in the Old Globe’s White Theatre at 7 p.m. Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Sundays; at 8 p.m. Thursdays-Saturdys; and at 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays through Sept. 6, 2015.

Welton Jones has been following entertainment and the arts around for years, writing about them. Thirty-five of those years were spent at the UNION-TRIBUNE, the last decade was with SANDIEGO.COM.