Jazz Duo Wins Olympic Gold

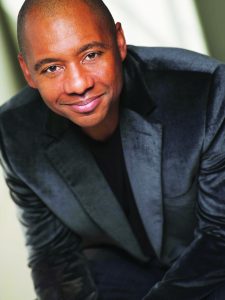

Saxophonist Branford Marsalis (photo by Palma Kolansky)

If you were searching for a convincing demonstration of that overused adage “less is more,” I would suggest a jazz performance by the exquisite duo of Branford Marsalis and Eric Revis. SummerFest 2012 presented the renowned saxophonist and bassist Wednesday (Aug. 8) on the second half of a program that opened with three pleasant but inconsequential chamber music pieces that featured saxophone.

Of course, Marsalis’ classical technique is so refined and fluent that any serious listener is charmed, perhaps even mesmerized, by his sinuous melodic turns. Indeed, he graced the tunes of four short pieces by Samuel Barber arranged for piano and soprano saxophone with gentle undulations that gave off an iridescent sheen.

When Marsalis, violist Paul Neubauer and pianist Jeffrey Kahane sprinted through Paul Hindemith’s rambunctuous Trio for Tenor Saxophone, Viola and Piano, Op. 47, I thought, “This would make a great mystery piece for music students to identify and analyze on a graduate school entrance exam.” But as Marsalis and his SummerFest colleagues led us through the disorganized, labyrinthine digressions of Adolf Busch’s Quintet for Strings and Alto Saxophone, Op. 34, I began to wonder if the whole classical saxophone project was worth the labor.

It took no more than 20 seconds of Marsalis’ unbridled yet limpid riffs of Philip Braham’s “Limehouse Blues” to establish the reason Sherwood Auditorium’s full house weathered the program’s odd first half and returned after intermission. It was that rare opportunity to hear an explosion of melodic invention and harmonic experiment unbound by the printed page and ignited by a combination of imagination and interior, volcanic fervor.

In Marsalis’ jazz mode, I sensed an immediate change in his sonority, although he certainly lost none of his finesse and sonic allure. It sounded richer, as if it were riding on a different air supply, a more vital energized propulsion that suggested the sexy vibrato and intensity of a great singer. As he strode about the stage in that lively dialogue with his bassist, the whole room woke up like a faint patient given a sharp dose of smelling salts.

Their selections covered the waterfront. From the heyday of Dixieland came their athletic, tongue-in-cheek take on “Tiger Rag” (1917), and for the sophisticates, a bebop tribute based on Thelonious Monk’s 1953 probing, abstract “Friday the 13th.”

For the sentimental, an extended fantasy on Hoagy Carmichael’s 1938 romantic ballad “The Nearness of You,” with Marsalis on tenor sax, matched with a plaintive take on “Body and Soul” (1930) that brought a rare, hushed concentration to the house.

As bassist, Revis conjured a hyperactive bass line that magically implied a whole bandstand of musicians. On reflection, a piano would have added much, as would have an ace drummer and guitarist, to mention some of the instruments that most jazz ensembles consider essential.

But when Revis and Marsalis were playing together, so much happened between them, it never occurred to me that anything was missing.

Their benediction was Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing.”

Ken Herman, a classically trained pianist and organist, has covered music for the San Diego Union, the Los Angeles Times’ San Diego Edition, and for sandiego.com. He has won numerous awards, including first place for Live Performance and Opera Reviews in the 2017, the 2018, and the 2019 Excellence in Journalism Awards competition held by the San Diego Press Club. A Chicago native, he came to San Diego to pursue a graduate degree and stayed.Read more…