Boxing as Ritual in Old Globe’s “The Royale”

The prime payoff of being a champion is savoring the absolute certainty that one is the very best at something. THE VERY BEST. Everything else is just job-related detail.

Jay “The Sport” Jackson is an African-American boxer in 1905 who wants to be heavyweight champion of the world. Everybody agrees he’s the best fighter around. But, at a time when plenty of living American citizens were once slaves, he’s the wrong color.

So, when finally he gets his title fight, the intense racial pressures are so frightening that even his supporters wonder if the reward justifies the risk of such chaos.

Jackson is unmoved. If he can be champion, he should. He must fulfill his destiny.

A simple-minded play on this subject, Marco Ramirez’s The Royale, is now on the Old Globe Theatre’s White Stage in a production more notable for its method than its message.

Based very loosely on the story of Jack Johnson, who in fact became the first black heavyweight champion in 1908, The Royale is a taut 80 minutes of stylized fantasy violence weighted with passions of power, sex, status and values.

As an intense metaphor for human survival, boxing has few equals. Pounding an opponent into submission leaves little room for interpretation. Theatricality is hopelessly superfluous. A film about boxing can achieve a degree of realism through technical trickery but plays about boxing never really work.

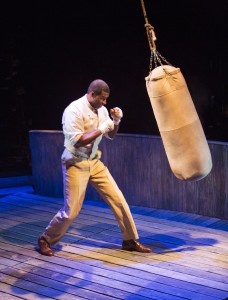

So Ramirez and director Rachel Chavkin have turned to choreography and ritual movement instead. No punches are landed or thrown. There is very little activity that could be called “boxing.” But the essence of the conflict is sufficiently suggested that the solemn resonance of the occasion can be mustered to make statements.

These, though urgent, are seldom more than predictable: It’s been a long, hard road. The frustrations are crushing. Evil is always threatening. Much can go wrong. Maybe this isn’t the right time. Etc., etc.

But this Jay Jackson is a true champion. He sees his prize and goes for it. End of story, not necessary of the show.

What’s interesting is the play’s public vocabulary, in between the private agonies. The story is told as ballyhoo from a ring announcer, emphasized by claps and hisses and grunts by the other performers, with an undercurrent of chanted instructions by the champ’s coach and punctuated by the piercing clap of the bell for each round.

The gimmick, awkward at first, soon settles into tense routine, persuasive enough that some audience members join in, as punches are exploded by movement and by blasts of explosive lighting.

Austin R. Smith has designed these blasts, and the rest of the raw, pushy lighting. Nicholas Vaughan’s scenery is intensely evocative, literal where necessary, and Denitsa Bliznakova’s period costumes seem to me ideal in every tiny detail. The production has a unified subtlety beyond anything in the script.

Chavkin’s staging is bold, self-assured and ultimately convincing. Would it support up a more nuanced, ambiguous script? Maybe not. But it would have been fascinating if Ramirez had given her some additional substance to deepen the violent little world she has constructed.

Robert Christopher Riley is every inch an acting champion here, light on his feet, flick-quick with his fists and bright of spirit. Respect and wisdom wreaths Ray Anthony Thomas, as the mentor who began learning the craft decades ago in vicious, blind-folded group combats with no rules except last man standing gets to sweep up the tips tossed into the ring. Okieriete Onaodowan is versatile and sincere as an upcoming apprentice.

John Lavelle represents the entire white race with economical angst, reading near to or far from the champ, as needed. And Montego Glover is a pert, spirited older sister, bringing the champ his inevitable load of guilt: “You’re ready to take over the rest of the world! Just don’t think the rest of us are.”

The true story of Jack Johnson, told in Howard Sackler’s 1967 play The Great White Hope and in many other versions, is far more complicated and fascinating than this meditation. This is not to say that The Royale is without merit. It shows, for example, that imagination and commitment can do wonders on stage. And that certain memories always are worth reexamining.

Continues at 7 p.m. Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Sundays; at 8 p.m. Thursdays-Saturdays; and at 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays through Nov. 2, 2014,

Welton Jones has been following entertainment and the arts around for years, writing about them. Thirty-five of those years were spent at the UNION-TRIBUNE, the last decade was with SANDIEGO.COM.