David Roussève’s ‘Halfway to Dawn’ Dances a Portrait of Jazz Great Billy Strayhorn

Billy Strayhorn, the American jazz composer, pianist, lyricist and arranger, liked to say, “I think everything should happen at halfway to dawn. That’s when all the heads of government should meet. I think everybody would fall in love.”

And Halfway to Dawn is the title of a layered dance portrait of Strayhorn, created by choreographer/writer/director/filmmaker David Roussève with his dance company REALITY.

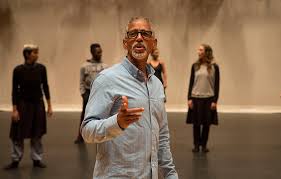

ArtPower presents the World Premiere of Halfway to Dawn. Image: Rose Eichenbaum

“It’s all set to a soundscape of Strayhorn compositions,” says Roussève, “and while there is projected text and video, this piece is propelled by movement and dance.”

The new work (presented by ArtPower at UC San Diego’s Mandeville, Friday, Nov. 9) shines a light on Strayhorn, who wrote or co-wrote more than 100 tunes for the legendary Duke Ellington, yet lived in the shadow of his famous employer.

Nicknamed “Swee’ Pea” for his mild manner, Strayhorn became a vital member of the Ellington Orchestra. With his classical training, Strayhorn created some of the most popular American music of the 20th Century, such as “Lush Life” and “Take the ‘A’ Train.”

Strayhorn never had a contract with Ellington and never hid who he was. He was comfortable living openly as a gay man, and Ellington accepted him and his bittersweet musical qualities.

“When we started making this piece, and working so closely with Strayhorn/Ellington music, I was sent back to my early experiences,” Roussève said. “It goes back to my jazz theater background, when I went to New York to do musical comedy and theater.

“I love working with Strayhorn’s rhythm and poly rhythm and phrasing, and it’s smart on its own. It’s nice to return to an old-school sensibility about dance and music and rhythm.”

The first act of the evening-length work is set in a Harlem night club. Dancers show off their unique personalities and styles. When performed on the diagonal, mini solos flash to the tradition of tappers jamming in the center. (view the video clip)

“There are moments when we are referring to all the recordings, the classic jazz, and then everyone gets to jam on their own for 24 counts,” Roussève said. “I love how jazz can go from really tight ensemble work, creating a community of music together, and then everyone gets to shine as a soloist. That becomes a core part of this piece.”

There are Broadway influences too: Step-ball-changes and barrel turns, and snappy foot swivels.

“I’m careful to make all the parts work,” Roussève said. “My father was a jazz musician in New Orleans,” Roussève said. “He played saxophone, and in this piece we don’t lose that wonderful ‘ticky-ticky’ sound and rhythm, which can happen in post-modern.”

Roussève’s expressionistic dance theater has been described as grief and joy hitting you all at once because it explores socially-charged and spiritual themes.

A magna cum laude graduate of Princeton University and Guggenheim Fellow, he has created dozens of works for his dance company REALITY and even more commissions for other companies. He’s also created short films. His dance awards include a Bessie and Horton Dance Awards. In 1996 he joined UCLA’s Dept. of World Arts and Cultures/Dance.

David Roussève during a Halfway to Dawn rehearsal. Image: Rose Eichenbaum

As a gay man of color, Roussève’s connection to Strayhorn is heartfelt.

“There is a clown character,” Roussève recalls, “and the clown and juxtaposition in the piece has a metaphoric meaning. It’s a core of Billy Strayhorn’s personality. He was a vibrant optimist on the outside. He’d always say ‘onward and upward.’ He was a beautiful smiling person, but people who knew him understood that things were complicated.”

Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1915, Strayhorn spent much of his childhood with his grandparents in Hillsborough, North Carolina. His mother sent him there to protect him from his father’s alcoholic rages. He became interested in music while living with his grandmother and playing hymns on her piano and playing records on her Victrola record player. He returned to Pittsburgh, studied classical music, and formed a musical trio while still a teenager.

Strayhorn worked at a drugstore to pay for piano lessons. When he made deliveries, he played for customers who had pianos.

While his ambition was to be a classical composer, as a black man 1930s he turned to the jazz world. He met Duke Ellington in 1938. Strayhorn worked for Ellington for the rest of his life, 28 years, until his early death from cancer. As Ellington described him, “Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine.”

Layering dance, text, video imagery and sound design, Roussève and nine Los Angeles-based dancers in the REALITY company have worked on this Strayhorn portrait for four years. The work also creates a dialogue on current social issues.

“Life is unfair, and depends on your life circumstances, when and where you are born,” Roussève said, “but Strayhorn was far ahead of his time, gay and out and living with his life partner in the late 1930s, which was unheard of and dangerous.

David Roussève’s company REALITY seeks to capture the “truths” of Billy Strayhorn’s elusive life by layering video-projected text and dancing to recordings of his songs from the 40s and 50s. Image: Rose Eichenbaum.

Roussève says Strayhorn had a close relationship with both Ellington and singer Lena Horne, but dancers don’t portray them in an obvious way. He prefers to tell the story like a pop-up book.

“There are handwritten footnotes projected over the dancers, to help guide the story,” he says, “ so you’ll get the life-death facts, his biography, but also who he is on an emotional level.

“Early on, we knew we wanted to use recordings with the aesthetic and technology of the 1950s. You’ll hear 11 songs from start to finish, and there’s a lovely sound terrain (by Sabela grimes) in act two that is abstract, to mirror Strayhorn’s complicated life.”

“He was a humble man. He also smoke and drank himself to death. Inside, he was a sad man. We try to capture the incredibly jovial and complex parts of this man. His favorite time to compose was 2 to 4 in the morning. Half way to the new day. He felt the most free and talkative then. His motto was ‘halfway to dawn.’”

http://artpower.ucsd.edu/event/david-rousseve-reality-halfway-dawn/

Sounds like an entertaining and interesting show, wish I could go