Critic at Large: A Sondheim Weekend in San Diego

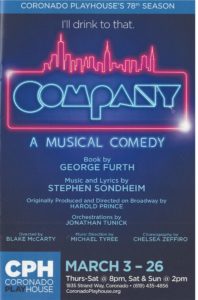

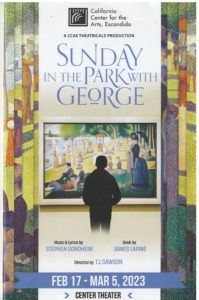

As I had no assigned San Diego theatre openings to cover this past weekend, I decided to explore two productions of musicals by Stephen Sondheim, one just opening and the other at its closing performance. As I admire and (mostly) enjoy Mr. Sondheim’s work, I thought that it would be interesting to compare two works with a male lead who is facing a turning point in his life. The two productions were Company, at Coronado Playhouse, and Sunday in the Park With George, at the Center Theater of the California Center for the Arts, Escondido.

Company (1970) is classified as Mr. Sondheim’s first musical that is not considered part of the “Golden Age,” a period in post-World War II America where musicals started tackling serious topics. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein were the most prolific composers of the period, and Mr. Sondheim was a protégé of Mr. Hammerstein. Arguably Company marked the point where Mr. Sondheim’s work came into his own. Company would be followed by Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), Pacific Overtures (1976), Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979), Merrily We Roll Along (1981), Sunday in the Park with George (1984), and Into the Woods (1986). “Woods” is thought to be one of the most-produced Sondheim musicals.

Company focuses on Robert, a single man who is about to turn 35. His friends, all married couples, have plotted to throw him a surprise party, though the beans are spilled as the play begins. For his married friends, Robert is “company:” he comes to visit when invited and is an entertaining guest. His friends want to marry him off, and they keep trying to find him women to date. Robert seems to have no problem in doing so himself, but the women in his life more-or-less pass through it. Robert claims repeatedly that he’s “ready” for marriage, but he seems to be more ready for one-night stands. The song, “Barcelona,” portrays him wearily and half-heartedly trying to convince a flight attendant to stay, rather than work her scheduled flight to the famed Spanish city. Robert is dismayed when his lovelorn begging turns out to be successful.

Company focuses on Robert, a single man who is about to turn 35. His friends, all married couples, have plotted to throw him a surprise party, though the beans are spilled as the play begins. For his married friends, Robert is “company:” he comes to visit when invited and is an entertaining guest. His friends want to marry him off, and they keep trying to find him women to date. Robert seems to have no problem in doing so himself, but the women in his life more-or-less pass through it. Robert claims repeatedly that he’s “ready” for marriage, but he seems to be more ready for one-night stands. The song, “Barcelona,” portrays him wearily and half-heartedly trying to convince a flight attendant to stay, rather than work her scheduled flight to the famed Spanish city. Robert is dismayed when his lovelorn begging turns out to be successful.

Robert also fights off offers of casual sex, including one of his married friends who wants a gay fling, and one from truth-telling Joanne, who’s one of the “ladies who lunch.” And, Robert’s friends are not terribly encouraging: “Watta ya want to get married for,” they sing. To me, the most telling song is “Sorry/Grateful,” which gives Sondheim and the husbands a chance to wonder at the contradictions of committed relationships: “You’re always sorry/you’re always grateful/you’re always wondering what might have been.” Robert does have an epiphany, but all it leads to is that he doesn’t attend the surprise party. What happens to Robert? We don’t know, but if there’s any connection to Mr. Sondheim’s own life, we can figure that marriage isn’t going to be part of his future.

George, the double lead (in 1880s Act 1 and also in 1980s Act 2) is also something of a loner – as well as obsessed with his art. We first encounter him experimenting with “design, composition, tension, balance, light and harmony.” He’s also working on depicting “reality,” a series of regular Sunday visitors to an island along the Seine River while tricking the eye with color combinations. His paid model, Dot, complains about the heat and about the need to hold her position. She’s also been his mistress, and it becomes more and more obvious that she is pregnant by him. She will eventually leave him in the company of Louis, a baker, who accepts her unborn child as his own.

George, the double lead (in 1880s Act 1 and also in 1980s Act 2) is also something of a loner – as well as obsessed with his art. We first encounter him experimenting with “design, composition, tension, balance, light and harmony.” He’s also working on depicting “reality,” a series of regular Sunday visitors to an island along the Seine River while tricking the eye with color combinations. His paid model, Dot, complains about the heat and about the need to hold her position. She’s also been his mistress, and it becomes more and more obvious that she is pregnant by him. She will eventually leave him in the company of Louis, a baker, who accepts her unborn child as his own.

Sunday does focus on intertwined relationships, as does Company, but George’s obsession is with his work, where Robert in Company, while clearly able to afford an Upper West Side apartment, seems not to be obsessed with his work at all.

In Act 2, the 1980s George is the great-grandson of Dot, the 1880s George having succumbed suddenly at age 31. Rather than embracing Pointillism, Great-grandson George has been struggling with other forms of it – technology-driven light shows created by a “Chromolume.” He’s finding that the contemporary art world is less concerned with technique than with status: Sondheim’s (pointillist) patter song “Putting It Together” comments on “the art of making art” as gathering financial and other supporters. Hardly the stuff of artistic invention, I think. And yet: the ghosts of the famous “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” painting that hangs in Chicago’s Art Institute return before the picture fades to white, what is described as a state of “so many possibilities.”

In Company, Robert’s epiphany causes him to take a “time out” from his friends. In Sunday in the Park with George, the great grandson’s epiphany also prompts him to “move on.” Perhaps, loneliness has its advantages.